Projects

How the Cossack Elite Lived, Earned Money, and Partied

How the Cossack Elite Lived, Earned Money, and Partied

The Business of Forgotten Ancestors project gives a voice and a face to those who have been erased from our memory by imposing the stereotype of a “peasant nation” on us. This is a series of stories about Ukrainian businesses and entrepreneurs from the time of the Cossacks and Hetmans. We are telling how the Ukrainian economic elite of the Cossack era was and how it LIVED.

Our first story is about the Kandyb dynasty. It could easily become the basis for a dramatic saga about several generations of one family. It has everything: ups and downs, conflicts and trials between relatives, serial poisoning attempts, and passionate, though apparently tragic love. And at least one magnificent wedding.

Why “at least”? Because we do not know the details of the others in this family history. In general, the wedding in question is unique. This is the only wedding of a Cossack foreman about which we know in detail what the guests ate, how many cattle they killed, and how many barrels of vodka they drank. Judging by the register of expenses, the party was impressive in its scope and lasted for more than one day.

The documents that formed the basis of this story have been preserved thanks to the Kandyb family archive. Some of them were published in the late nineteenth century by the historian Oleksandr Lazarevsky, the great-grandson of the bride at that wedding, in the “Memoirs of the Konotop Zemstvo.” The rest of the family documents of the Kandybs and their descendants are now stored at the Institute of Manuscripts of the Vernadsky Library.

We will tell you about the fate of four generations of Kandybs and how business was organized in Ukraine in the Hetmanate more than 300 years ago. What goods our lands were famous for back then and why, instead of trading grain with Europe, our ancestors distilled vodka from it and sold it to the West in 500-liter barrels.

And at the end of our story, we will also reveal how Taras Shevchenko’s cigars are connected to all this history.

Let's start the story!

Actors

Kandyba

Kandyba

Kandyba

Fedir Andriyovych Kandyba

Andriy’s son, who squandered his father’s money

Kandyba

Anastasia Kandyba and Petro Lashchynskyi

Vadim Nazarenkod

How the loss of the homeland turned into

a new chance

1675. Years of continuous warfare after Khmelnytsky’s death turned Right-Bank Ukraine into a scorched desert. Among the thousands of refugees fleeing the devastation of Ruina was the former Korsun colonel Fedir Kandyba. He left his hometown with a heavy heart, as Korsun was not just his home, but the place of his power and status.

When Fedir moved to the Left Bank, to the Konotop Hundred, he hoped that it would only be temporary. That the war would soon be over, and he would be able to return to his Korsun, rebuild what had been destroyed, and become the man he was again. But life had other plans for him — Konotop region became his new homeland for the rest of his days.

And to his credit, Fedir did not give up, but began to build a new life. In a few years, this experienced manager managed not only to get back on his feet, but also to found his own sloboda, Kandybivka. In 1681, he was appointed Konotop centurion, and when Ivan Mazepa came to power, Fedir also received the village of Kurylivka.

Success brought new opportunities. Fedir climbed the career ladder higher and higher until he got the prestigious position of regimental cart driver in Nizhyn. At the same time, his son Andrii became a centurion in his place, and the Kandyb dynasty became firmly entrenched in the circles of power. And when Andrii married Dominikia, the daughter of the influential Chernihiv colonel Lyzohub, the family strengthened its status in the Cossack elite.

In 1700, Fedir died, leaving his son a solid inheritance: estates, connections, and reputation. Andrii Kandyba inherited not only his father’s property, but also the power over the Konotop Sotnia, an administrative unit of the Nizhyn Regiment that covered the town of Konotop and dozens of surrounding villages and hamlets. The power of the sotnyk was absolute. In today’s language, a sotnyk was the head of the district administration, the head of the police, and a judge in one person, and during wars he also commanded the Cossacks of his hundred. It was a power that modern officials can only dream of.

Starting a family business

and losing political office

Andriy Kandyba was not going to limit himself to positions of power. With the Konotop Hundred and his parents’ estates in his hands, he launched an active economic activity, producing and trading vodka, tobacco, and tar. But the real money was not in production, but in the monopoly on sales.

In the Hetmanate of those times, there was a system of redemption known as “lease” — one could buy back the monopoly right to trade certain goods, primarily vodka. In 1704, Andrii and his partners made a real investment for the future: they “leased” all the “vodka, tobacco, and tar hams” in Konotop. The price was 4000 zlotys, an amount that could buy several water mills. But this was a long-term calculation: the monopoly was to bring much greater profits.

When the Great Northern War broke out and Hetman Mazepa sided with Swedish King Charles XII against Peter the Great, the Cossack army began to control the territories on the Right Bank. Again, the lands that had once been under Khmelnytsky’s rule were temporarily united. Then the rebellious hetman appointed Andriy as colonel of Korsun. The symbolism of this moment can hardly be overestimated: the son of Fedir Kandyba returned to his small homeland, which he left as a child, to take the same position that his father once held. The difference between a centurion and a colonel is a real leap in the hierarchy of power.

But Andriy Kandyba did not take part in the fighting of the Northern War, and he was not on the field of the Battle of Poltava either. However, after Mazepa’s defeat, a denunciation was written against Andriy Kandyba in 1710. The Korsun colonel was arrested and sent to Moscow for his ties to the hetman, whom Peter the Great called a “traitor.”

Five years away from Ukraine changed his life forever. When Andriy finally returned to the Hetmanate in 1715, he was allowed to engage in only economic activities, and was forbidden to hold political office. The former colonel returned to the place where it all began, to his father’s Konotop Hundred. Now all his efforts had to be directed not to the government, but to what was left: his farm and estates. Fate turned the politician into a slave businessman.

The story of oxen and diamonds

or how Andriy's son squandered a lot of money

1718. Andrii Kandyba entrusted his eldest son Fedir with an important trade operation — the sale of oxen in distant Gdansk. The lot was impressive: three hundred fattened bulls. Each was paid the equivalent of 20 rubles or 100 zlotys-four to five times more than in the Hetmanate. In total, young Fedir ended up with 6,000 rubles-a real fortune for those times.

But instead of returning the money to his father, Fedir decided to “live a nice life.” He bought expensive goods that his father had not asked for: foreign fabrics of the best quality, silverware, and elite alcohol. He spent especially lavishly on jewelry for his wife-two large gold chains, twenty strings of pearls, and three diamond rings.

Among the items we bought were “sugar snacks,” a real luxury of the time. Cane sugar, the only one known at the time, cost a lot of money. In the middle of the eighteenth century, a puddle of sugar (16.4 kg) at the fair in Romny cost about 9 rubles. For comparison, Ivan Kotliarevskyi’s grandfather bought a whole yard in Poltava for 27.5 rubles.

The foot with the coat of arms of the Oleksandrovychs

Fedir was sure that he would resell some of the goods at the fairs and make even more money. He took his treasures from one fair to another-first to the Epiphany Fair in Kharkiv, then to the Shrovetide Fair in Romny, and then back to Kharkiv for the Trinity Fair. But Andrii Kandyba’s son had no entrepreneurial spirit and “wasted those goods in vain”.

When Fedir returned home without any money, his father caused a real scandal. The quarrel escalated to a fight — the son pushed his father in the chest so hard that he almost fell over. “Stop chewing on me! I’m not going to borrow money from you! I’ll pay you back when I have it!” said the furious Fedir.

The resentment was so deep that Andriy Kandyba filed an official complaint against his son, which was recorded in the Konotop government’s books. But despite this scandal, the family relationship between father and son did not break down — blood was stronger than money.

How Efrosynia, Kandyb's daughter-in-law,

tried to poison both her husband and his family

Fedir Kandyba’s wife, whom he bought jewelry and “sugar snacks” for with his parents’ money, was named Yefrosynia. They got married in 1718, the same year as the scandalous story of the oxen. The girl came from an influential family: she was the daughter of Andrii Horlenko, the Hetmanate’s general chorunzho (boss). But despite her high rank, the Horlenko family did not have much money, and Yefrosynia brought a small dowry to her new family.

Andrii Kandyba wanted his son to have richer matchmakers, but he did not listen to his father. Was it true love? Or was it just a youthful rebellion against his father’s will? It is not known. But what happened next exceeded the old Kandyba’s worst fears.

Love is love, but a year after the story of squandering money for oxen, Yefrosynia tried to poison her husband and all other members of the Kandyb family. Her motives remained unknown and unclear. The woman justified her madness, but who knows what was really behind it.

There were several attempts to poison him, and each one was thought out in its own way. Efrosynia put “tinder” in her husband Fedir’s food and drinks three times. Her father-in-law and mother-in-law got it once. But she prepared the most original plan for her husband’s brothers and sisters-in-law.

Efrosynia brought them gingerbread with poison as a present. It was a perfect plan, because gingerbread at that time was a luxury pastry and was considered an expensive gift. At Easter and Christmas, it was customary for members of the city magistrates and shop managers to bring gifts to the townspeople, called “going to the ralets,” and gingerbread was often among the gifts. Who would suspect a death trap in a holiday treat?

It is not known what kind of poison it was or if it was poison at all, but no one died. Yefrosynia decided to try again, but she was caught. The nanny of Yefrosynia’s child found out about the preparations for the crime and told Kandyba Sr. He searched his daughter-in-law’s room and found a “flask of tinder”. Yefrosynia began to make excuses that it was a cure for “female weakness,” but she refused to drink it in front of her father-in-law…

Penitential receipt

and a cross from illiterate Efrosinia

Andriy Kandyba forgave his daughter-in-law and did not take the case to court. After all, she was the mother of his grandchildren. He confined himself to repentance, including written repentance, where she confessed and repented of everything.

Of course, we know about Yefrosynia the poisoner only from her “penitential receipt,” which was kept by her father-in-law. The document was written by a priest from Konotop in the presence of the Kandyb family. Although Yefrosynia was descended from a Cossack elder, she could not write, as most women of that time did. Therefore, she put a “cross” under her own confession.

At that time, the majority of the population was illiterate, so paperwork was usually done by clerks or other educated people. At the end, the formula “and instead of his illiterate scribe N. put his hand” appeared. When a person knew how to write, the document was marked “RV” – “with his own hand.”

It is not known what Yefrosynia could have written if she had been literate. Women’s voices often go unheard in the past. Therefore, it is difficult to judge how objectively and fully all the details of this amazing story are reflected.

Mother-in-law, daughter-in-law and 800 rubles

family war and division of property between grandchildren

In 1725, the Russian Empire remembered Andriy Kandyba’s military and managerial experience and engaged him in the Gilian campaign in the Caucasus. He stayed there for four years. During this time, his eldest son Fedir died: he was carrying vodka to Astrakhan to sell, fell ill on the way and died. Death took away his eldest son and main heir.

In 1729, Andrii returned from the campaign. For his merits, he was appointed judge general of the Hetmanate, a very high position. But fate was preparing another cruel irony: he lived in his new status for only a year. In his will, which Andriy Kandyba made in 1729, he left everything to his wife Dominika, who could give something to his descendants at her own discretion.

But the main thing is that my father did not forget the insult. The will clearly stated that the wife and children of the deceased Fedir would not receive any property. Andrii remembered the story with the oxen, the fight, and the attempted poisoning. Forgiveness is forgiveness, and inheritance is inheritance.

Meanwhile, Fedir’s widow Yefrosynia remarried and… declared war on her mother-in-law. The reason for the conflict was money for vodka. According to her, Kandyba Sr. sold six 500-liter barrels of vodka that belonged to his deceased son and made 800 rubles. He gave only 118 to his daughter-in-law. In addition, Yefrosynia demanded that Dominika provide financial assistance to her grandchildren. The litigation lasted for years. It ended when Yefrosynia died. She died without getting what she wanted.

After that, Dominika Kandyba decided to take control of the fate of her grandchildren-two boys and two girls orphaned after the deaths of her wayward son Fedir and her conflicted daughter-in-law Yefrosynia. With the boys, Andriy and Oleksandr, she tried to be kind: she hired private teachers and sent them to study at a college. But in vain. The boys ran away from school, and later committed several “infamous acts” and disappeared into the unknown. Oleksandr even robbed his own grandmother. In her will of 1749, Dominika admitted that she knew nothing about the present fate of her grandchildren.

But the situation with her granddaughters, Anna and Anastasia, was much better. Although their grandmother did not leave them any landed property, she married them off with dignity and gave them a generous dowry.

Dominika left all of her main property to her son Danylo, who could help his relatives at his own discretion.

It was to Danylo that Dominika handed over both the registers of matchmaking expenses and the wedding of her granddaughter Anastasia, which we describe below. These unique documents, later published by historians, give us a rare glimpse into the world of luxurious celebrations of the Cossack officers.

Cattle are beaten, vodka is poured, and gifts are given out

a luxurious wedding of the Cossack elite of the 18th century

After all the family dramas and court battles, it was time for a joyful event — the wedding of Anastasia’s granddaughter. The groom was Petro Lashchynsky. The grandmother spared no expense for the lavish celebration. Despite all the conflicts with her daughter-in-law and disappointment in her boy grandchildren, Dominika Kandyba decided to give her granddaughter a decent marriage.

Marriage in those days was traditionally divided into two major stages: matchmaking and wedding. The matchmaking was an official meeting between the groom’s representatives and the bride’s family to reach an agreement to marry — a kind of “signing of the contract” between the families. If an agreement was reached, the matchmaking ended with an engagement. A wedding was a church wedding and a multi-day lavish celebration. But the matchmaking was also accompanied by solemn feasts.

Matchmaking:

80 rubles for food, drinks and gifts

The register of expenses for the engagement of Anastasia Kandyba and Petro Lashchynskyi shows that everything ended with a big banquet. Representatives of the Cossack officers and clergy were invited.

It is also known that the guests consumed 6 rubles worth of fish and caviar (caviar), 2 rubles worth of various condiments and groceries, and 5 poods of butter (mostly used to make pates).

One can only guess how many guests there were. And it is not known how many days the matchmaking was celebrated. There could have been more than one banquet. In total, Anastasia Kandyba’s matchmaking cost her grandmother Dominika more than 80 rubles. Most of the money was spent on alcohol and food. The groom, Petro Lashchynsky, and his relatives were presented with expensive clothes. Anastasia Kandyba’s future husband received an expensive Italian scarf worth 2 rubles from her grandmother, and his mother and sister received a spare (2.4 rubles and 1.4 rubles).

Gifts were also given to invited guests, including the regimental sergeant major and the Konotop centurion of the time. Two towels as a gift to the starostas are also mentioned in the expense column, which means that the matchmaking began traditionally and in the same way as the peasants. Local musicians also earned money during matchmaking. They were paid 4 rubles. It is not known how many musicians there were, but their earnings for matchmaking were equal to the annual earnings of a hired hand in the village at that time.

Wedding

a loaf costing as much as an ox

Anastasia Kandyba’s wedding for her grandmother was much more expensive. A lot of money was spent on other products: bread and pastries, spices, eggs. A wedding loaf alone cost 4 rubles, which was the price of an ox in the Hetmanate and the amount a hired hand could earn in a year.

Spices and groceries were not cheap. Cloves, saffron, ginger, raisins, figs, olives, rice, lemons, and lemon juice cost 5 rubles. The musicians earned more than at the matchmaking. This time they were paid 7 rubles.

For the guests’ feast, the following were slaughtered:

There was also a lot of alcohol:

• 3 barrels of beer

• 30 quarts of Sudak wine

• 6 quarts of “cinnamon sugar vodka”

• 6 quarts of strong “sugar vodka”

• 5 quarts of “lemon sugar vodka”

• 5 quarts of “orange vodka”

• 8 buckets of anise “vodka”

• a kufa of simple vodka (500 liters)

• 120 quarts of cherries

There was also a lot of alcohol:

• 3 barrels of beer

• 30 quarts of Sudak wine

• 6 quarts of “cinnamon sugar vodka”

• 6 quarts of strong “sugar vodka”

• 5 quarts of “lemon sugar vodka”

• 5 quarts of “orange vodka”

• 8 buckets of anise “vodka”

• a kufa of simple vodka (500 liters)

• 120 quarts of cherries

In addition, the groom’s family and wedding guests also received gifts. Petro Lashchynskyi again received an expensive shawl, and the boyars and starostas also received shawls.

It is not known exactly how many guests attended the wedding. We can only guess from the amount of alcohol drunk and bread consumed — 100 loaves of bread and 80 sittings.

How much wealth did the bride Anastasia Kandyba

bring to her husband's family?

In total, Dominika Kandyba spent more than 300 rubles on the matchmaking and wedding of her granddaughter Anastasia, but the dowry cost even more. The size of the dowry depended on the family’s wealth.

Do you remember that old Andrii Kandyba and his wife once did not want Yefrosynia, Anastasiia’s mother, as a daughter-in-law? Because she brought a small dowry with her.

Yefrosyniia’s dowry consisted of:

For comparison, the dowry of Anastasiia Kandyba, Yefrosyniia’s granddaughter, was much larger.

Anastasiia Kandyba’s dowry:

5 expensive kontushes,

4 skirts, 5 aprons

6 spoons, 6 glasses, 3 cups

gold chain, 6 strings of pearls

3 bedding sets”

35 women's shirts, 30 scarves

horse, 2 mares, 3 bulls, 3 cows, 2 oxen, 30 sheep

In general, the dowry was more expensive than the matchmaking and wedding itself. In wealthy families, dowries for daughters were often a fortune. For example, Stepan Tomara (whose son was taught by Skovoroda) gave his three daughters a dowry of more than 18,000 rubles. Even 300 years ago, Ukrainians knew how to party, but they were also good at counting money.

Epilogue

Kandyb's trail in the nineteenth century and Shevchenko's cigars

The history of the Kandybs did not end with the eighteenth century. Their descendants remained wealthy and influential for a long time. One of their descendants was the three Lazarevsky brothers, the great-grandchildren of Anastasia Fedorivna Kandyba, the bride from our wedding story. Vasyl was a writer and translator, Oleksandr was a scholar and historian, and Mykhailo was a government official.

In the mid-nineteenth century, the Lazarevskys became a well-known intelligent family that left a mark on the cultural and scientific life of Ukraine. By the way, Oleksandr Lazarevsky is the historian who preserved the Kandyb family heritage in archives and documents for us.

But Mykhailo was given his diary by none other than Taras Shevchenko. The Lazarevsky brothers were friends with the poet and were his patrons. They helped the poet in the most difficult periods: they supported him financially, gave him money, and gave him the small pleasures of life.

For example, Shevchenko recalled that in June 1857 he received 75 rubles from Oleksandr Lazarevsky, and later cigars. Thus, the story of the Cossack foreman Kandyb unexpectedly closes with the fate of the greatest Ukrainian poet.

The family, which once built businesses and organized loud parties, became part of the circle that supported Shevchenko and created a new Ukrainian culture several generations later.

Date of publication: September 7, 2025

© 2025 All rights reserved. LIGA BusinessInform News Agency

© 2025 All rights reserved. LIGA BusinessInform News Agency

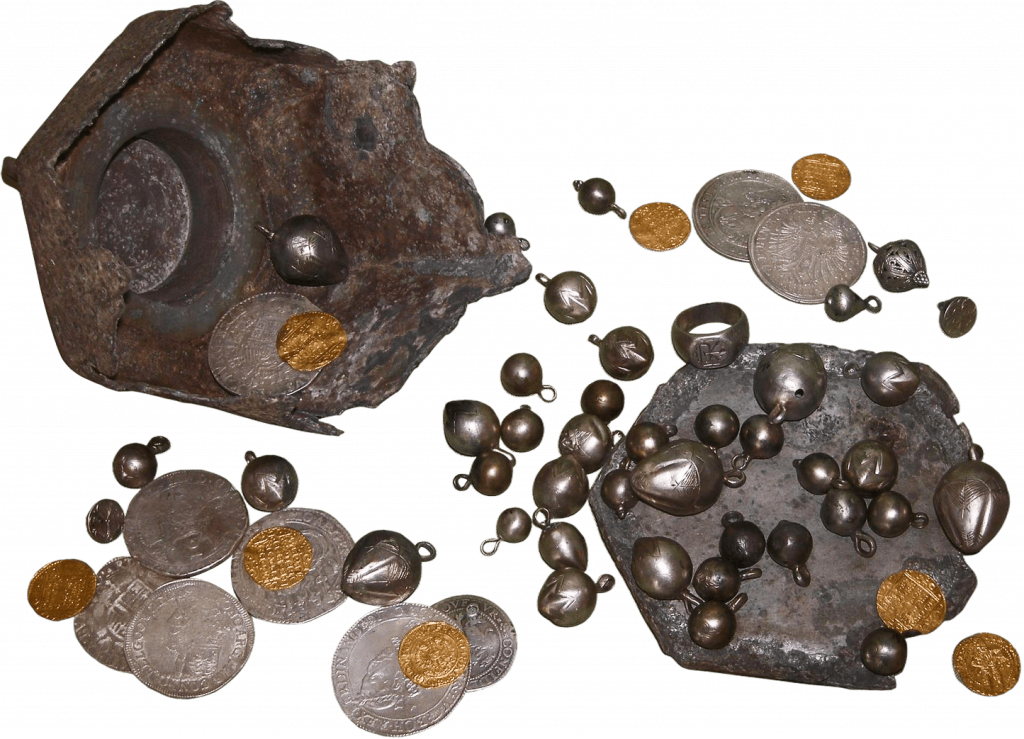

The historical artifacts depicted in the publication belong to the collection of the National Museum of the History of Ukraine

Illustrative images were generated using the AI models Sora and Recraft.ai

Projects is proudly powered by WordPress