Projects

A Portrait with a Scalpel

soldier’s face

Written by Tamara Balaieva

Photos by Vasyl Salyha

Layout by: Yuliia Vynohradska

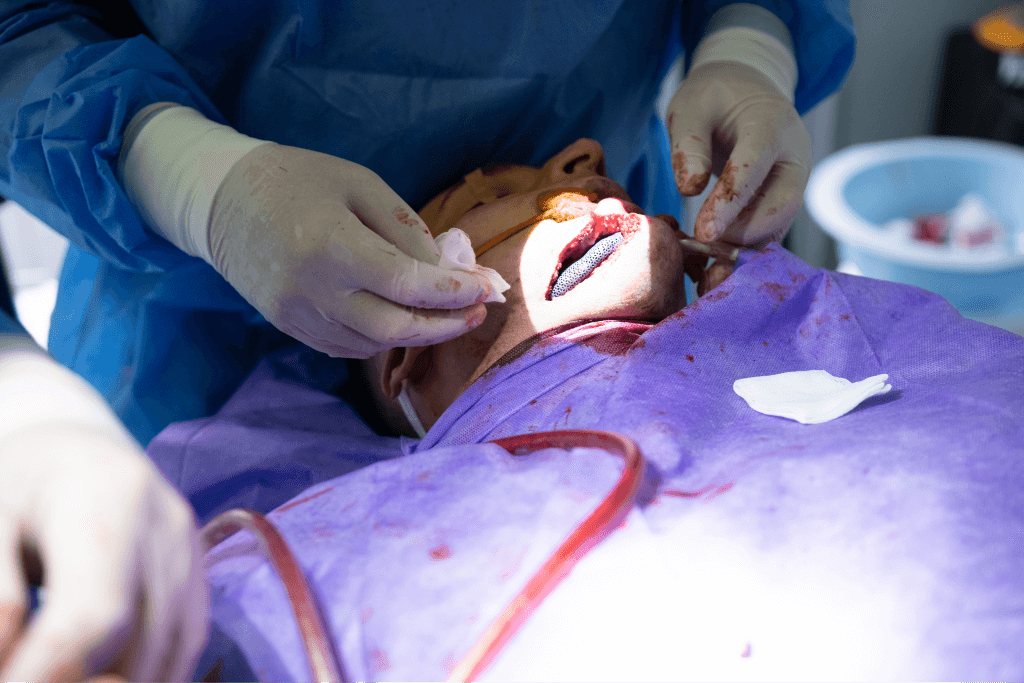

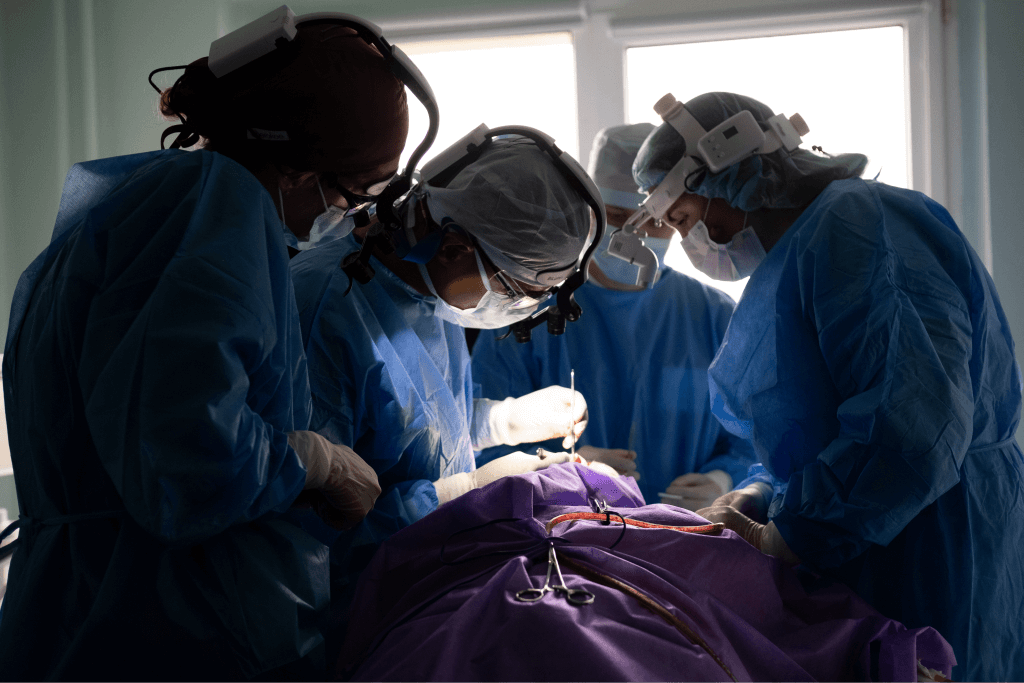

In late April, a Face to Face mission of American plastic surgeons came to Lviv. In a week, the doctors performed free-of-charge facial reconstruction surgeries on 26 Ukrainian soldiers.

All of them had extremely complicated injuries, such as a missing nose or jaw or broken bones.

One of the patients was Illia Svirhotskyi. The 23-year-old was called up on 15 March 2022, and on 27 April, a tank shell projectile hit him in the face.

Illia’s eye got wounded, the bone underneath shattered, and his nose completely demolished. He could not see with one eye and could not breathe through his nose.

LIGA.net spoke to Illia and the Face to Face mission doctor.

It felt like he was hit in the face with a sledgehammer. Illia fell down and wanted to touch his face with his hands.

But, in a split second, he realised he could not: His hands were dirty, and the wound, judging by the fact that everything around him in the trench was immediately covered with blood stains, was open. One of his eyes couldn’t see at all.

The guy could feel his jacket soaking in blood. He felt for the first aid kit. As best he could, he wrapped his face in bandages and injected himself with painkillers, even though he felt no pain.

Listening to the sounds of explosions, he waited for the fighting to end. All that time, Illia was shaking, and at times he thought he was going to die.

But he survived.

Illia, a 23-years-old from the city of Kamianets-Podilskyi in western Ukraine, completed his military service in 2020 and went back home.

He worked as a sales agent and was about to marry his girlfriend Olha. He planned to live a happy life with the usual worries, such as work and home improvement…

Over the course of a year, Ilya underwent ten surgeries, the last one being a nose reconstruction at Face to Face. Now he can breathe normally and see with both eyes, although poorly. And his nose has almost returned to its original shape.

A military medical commission has deemed Illia partially fit for military service, meaning he will continue to serve but not participate in combat. His military story is not over.

How did Illia’s life change after his injury and what does it feel like to constantly see the consequences of war in the mirror?

There is a war here

Thursday was the hardest day in Illia’s work. He delivered groceries by car to grocery stores, and on Thursday, the route was always the longest, and the most products had to be delivered for the weekend.

On Thursdays, Ilya would always come to work at six in the morning. It was the same on the Thursday of 24 February 2022.

“I hadn’t even woken up yet, I hadn’t even picked up the phone,” Illia recalls, “I arrived at work sleepy, about to go out on a route, and then the director called and said that the war had started and we were not working today.”

Ilya’s first thought was, “Olia is studying in Ternopil, I need to go and pick her up immediately.”

His second thought was, “I would definitely get a call from the military enlistment office and be told to go and fight.”

Over the next few days, he mentally prepared himself for this call. And every morning, he waited for it more and more so that he could finally feel a sense of certainty.

“The military enlistment office called on 15 March. They told me to pack and come the next day”

The military enlistment office did call on 15 March, telling Illia to pack up his things and come the next day.

In the evening, Illia packed a warm jacket, slippers, a toothbrush and toothpaste, and a bar of soap into his bag. He checked that there was a chain with the Mother of God hanging around his neck, a gift from Olia.

The next morning, he went to the military enlistment office and, on the same day, along with other guys, went to Mykolaiv for training.

The training lasted for two weeks, and in early April 2022, illia and the other guys were sent to the Donetsk region – first to Sloviansk, and from there, to Izium, in the Kharkiv region.

On 10 April, Illia and his group arrived in Dovhenke, a village in the Izium district of the Kharkiv region.

The next day, Russian troops launched an offensive against the village, with fierce fighting lasting until mid-June. Dovhenke was important to the Russians because it served as a springboard for an offensive to the city of Sloviansk.

For Illia, Dovhenke was the place where he first took part in combat and got wounded to the face three weeks later, something that many have changed his looks forever but probably saved his life.

A blow with a sledgehammer

On 26 April, two days after Easter, Illia’s group once again moved to the positions. They took a lot of food with them, hoping the duty would go smoothly.

But in the morning of 27 April, the Russians began to advance.

Illia remembers being in a trench and simultaneously hearing an explosion, feeling as if he had been hit in the face with a sledgehammer. It was a projectile from a tank shell that exploded near the trench.

Then, everything happened very quickly.

He remembers putting the inside of his jacket to his face, realising it would not stop the bleeding, and grabbing a first aid kit. He injected himself with painkillers, even though he didn’t feel any pain, and rewound his face.

He remembers how a fellow soldier ran up to him and helped with bandages; how he realised that he couldn’t see with one eye and couldn’t blink, which meant the wound was open; how he felt the skin under his eye had been torn and the bone damaged; that the place where his nose used to be a few minutes ago feels strange, as though there was nothing else there.

He remembers looking around with his other eye, seeing that everything in the trench was covered in blood – his blood; realising he had been hit in the face and would probably never look the same again – maybe wouldn’t survive at all.

He felt himself shaking.

“Illia felt as though he had been hit in the face with a sledgehammer”

When everything around him quieted down, Illia realised that his arms and legs were not damaged and he had to run to the evacuation point, where he and the other wounded could be taken by a car.

It was about three kilometres away, and so he ran.

“Then three or four other people were wounded, and they could not walk on their own, they were carried,” Illia recalls. “Finally, we ran to that car and were taken to the medical centre in Dovhenke.

“There, they bandaged us properly, or maybe they washed us; I don’t remember. When we were being bandaged, there was fighting in all directions again, and a shell hit our medical unit. But fortunately, the basement was strong, and nothing happened to us.”

In the medical unit, Illia’s face was completely bandaged, including both eyes. The doctors explained that the projectile hit Illia’s nose inside his skull, crushed the bone under his eye, and damaged his eye.

“I could only breathe through my mouth, but it didn’t bother me much at the time – I was just glad to be alive,” Illia recalls.

“They put us in a car and drove us somewhere. I could not see anything because of the bandages on my eyes. I could only feel the doctors examining me again in the car, injecting me with something, putting me on a drip.”

Eight surgeries

Illia and his comrades were brought to a hospital in the city of Kramatorsk. The doctors there partially removed the projectile from his face, bandaged him again – covering only one eye now – and sent him to Dnipro.

“When I came to, I realised my face had changed, and I would not look the same,” says Illia.

“I called my family and told them that I was fine. That I was wounded, but everything was fine. Olia, my fiancée, was crying.”

“Do you remember the first time you looked in the mirror after being wounded?” I ask.

“Yes, I do. I was swollen and took a picture with my phone. But I wasn’t really worried about my appearance, only about my eye, that I might never be able to see again; and about my nose, that I would not be able to breathe.

“But in general, I was thinking: I’m alive, and thank God.”

Illia pauses, and then, in a steady voice, goes on, with a subtle smile on his face.

“There was another moment. There were interns in the hospital in Dnipro. And when I was already on the surgical table, one of them looked at me and said, ‘Wow,’ and took out his phone and took a close-up photo of my face.”

Illia changes the topic without a pause.

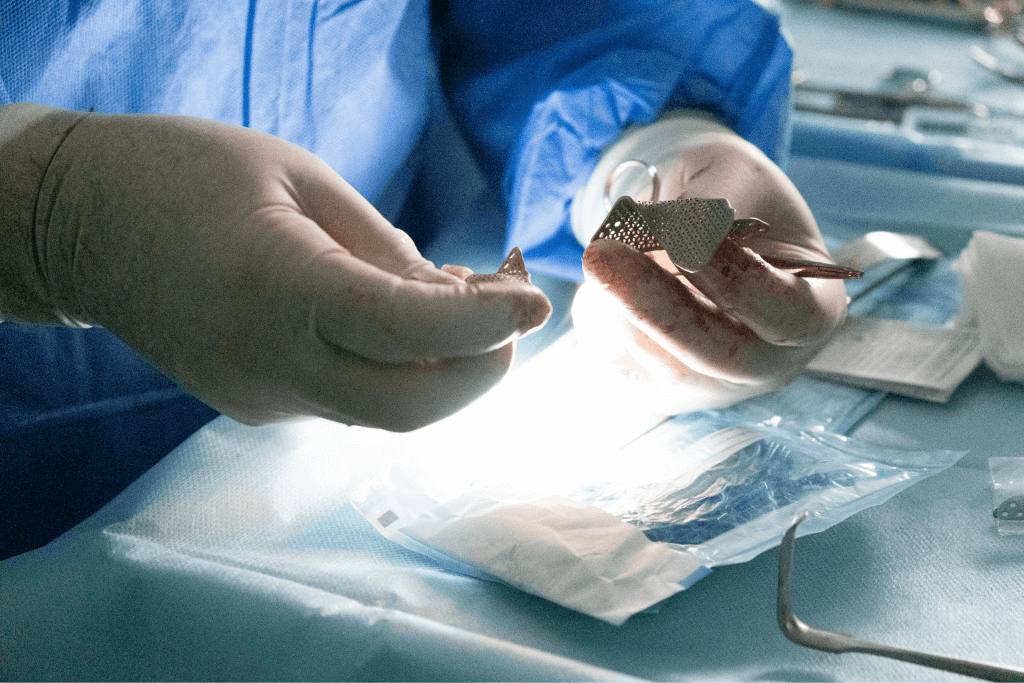

“Well, and after the surgery, the doctors came and said that they had put temporary titanium plates in place of the bone under my eye to keep my face in shape. They warned me that they had to be replaced quickly, because they would not take root and there would be inflammation.

“Then the ophthalmologists came and said: there is a 10-percent chance that I will be able to see with that eye. And that was it. Then I was sent to Lviv.”

In Lviv, Illia underwent five more surgeries. The doctors took out the titanium plates that were placed in Dnipro, and worked on his eye and nose.

“I don’t understand what they did to me, but I started breathing and was finally able to sleep on my side.

“Before that, I slept only on my back. When I turned to my side, fluid mixed with blood would flow from my nose.”

Saving the nose

In Lviv, Illia saw his fiancée and his mother for the first time since his injury when they came to the hospital.

He immediately beams when recalling the moment.

“It was something incredible! Olia didn’t leave my side, she watched and cried. She said she loved me and wouldn’t let me go anywhere else.”

Next came treatment in Poland and more surgeries. The doctors prepared individual titanium plates for Illia and inserted them under his eye and partially into his nose instead of bone. Those would remain in his body for life.

After returning to Lviv, Illia underwent another medical examination, followed by a sanatorium in the resort city of Truskavets, in western Ukraine, and a military medical examination.

The military medical commission deemed him partially fit for military service, meaning he will continue to serve but not participate in combat.

“All the time afterwards I was in my military unit in Zhytomyr,” says Illia, “I felt much better, my wounds healed, I could breathe through my nose and see a little with my [wounded] eye.”

“However, my nose did not look very good – it was flattened and not very similar in shape to a nose. But I didn’t care. I knew that Olia loved me the way I was.”

In March 2023, Illia, as usual, was on duty in a military unit in Zhytomyr. His doctor called him and said, “There’s a Face to Face program where American doctors come and perform facial plastic surgery on Ukrainian soldiers. They can help you with your nose. Send your documents; maybe you will be selected.”

Illia did send the documents, and on 19 April, he left Zhytomyr for Lviv to meet with the American doctors.

57 patients with facial injuries

In April 2023, nine American doctors and eight nurses came to Lviv to perform facial surgery on 26 Ukrainian soldiers. The mission, called Face to Face, was initiated by the American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery and the organizations Razom for Ukraine and INgenius.

This was the second mission of American doctors to Ukraine during the full-scale war. The first one took place in September 2022 in the western Ukrainian city of Ivano-Frankivsk, when 31 people, both military and civilians, who suffered from the war, underwent facial surgery.

Both times, the Americans were brought to Ukraine by Ivanka Nebor, an ENT doctor who completed her internship and worked for a year at the Institute of Otolaryngology in Kyiv, and three years ago went to study in the United States.

Before moving to America, Ivanka founded the medical NGO INgenius, which promotes evidence-based medicine and organizes training events for doctors. In July 2022, Ivanka received a phone call from her friends at the American-Ukrainian foundation Razom for Ukraine: “We have been approached by ENT surgeons from the American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. They already have experience of traveling on humanitarian programs to South America, Africa and India. Now they want to go to Ukraine and are looking for local partners to carry out the mission with. Will you help them?”

“I was very excited about this idea,” says Ivanka. “Because before that, I was approached by doctors who wanted to operate on Ukrainian soldiers but were not ready to go to Ukraine, they wanted to do it somewhere in Poland. A mission to Ukraine is much better, because patients can have their families with them. Plus, it’s training for Ukrainian doctors and help for hospitals as the equipment the Americans bring remains with them. And another thing is that it is much cheaper to have surgeries in Ukraine than abroad.”

Ivanka contacted the surgeons and immediately began organizing the first mission. Preparation takes about three months: one and a half months are spent just selecting patients. Before the first mission, the organizers received 50 applications, and 31 people were selected. These were soldiers who had been injured during combat missions and civilians whose homes had been hit by missiles.

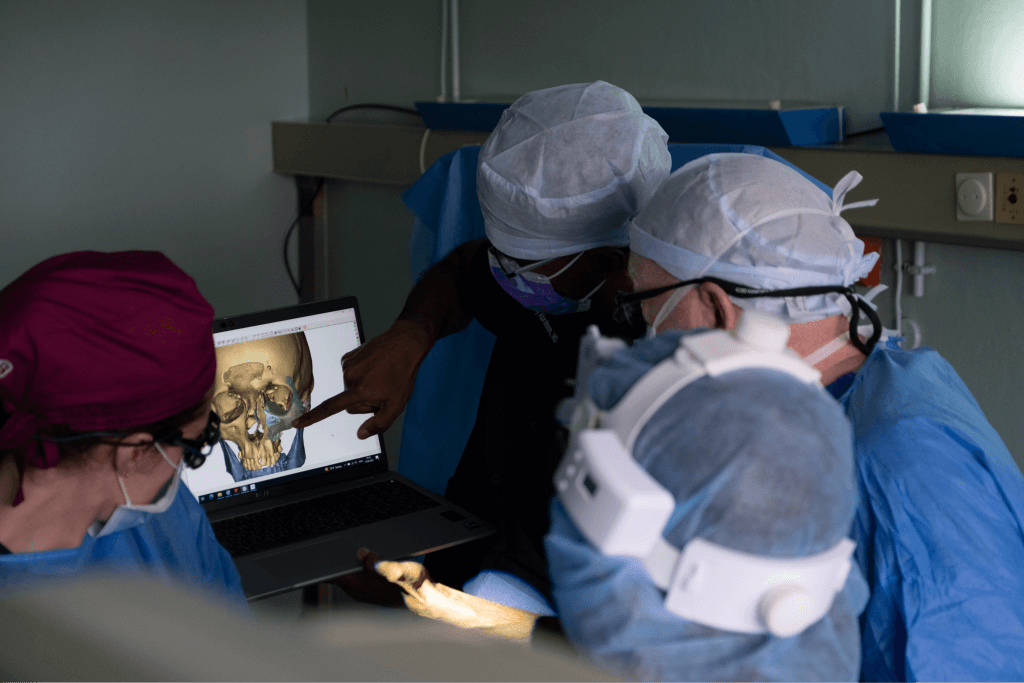

“We immediately identify patients who need to have their eye orbits reconstructed with 3D implants,” explains Ivanka. “They are very expensive, but a Belgian company prints them for us for free. Many Ukrainians work there, and they persuaded their bosses in Belgium to do it for free.”

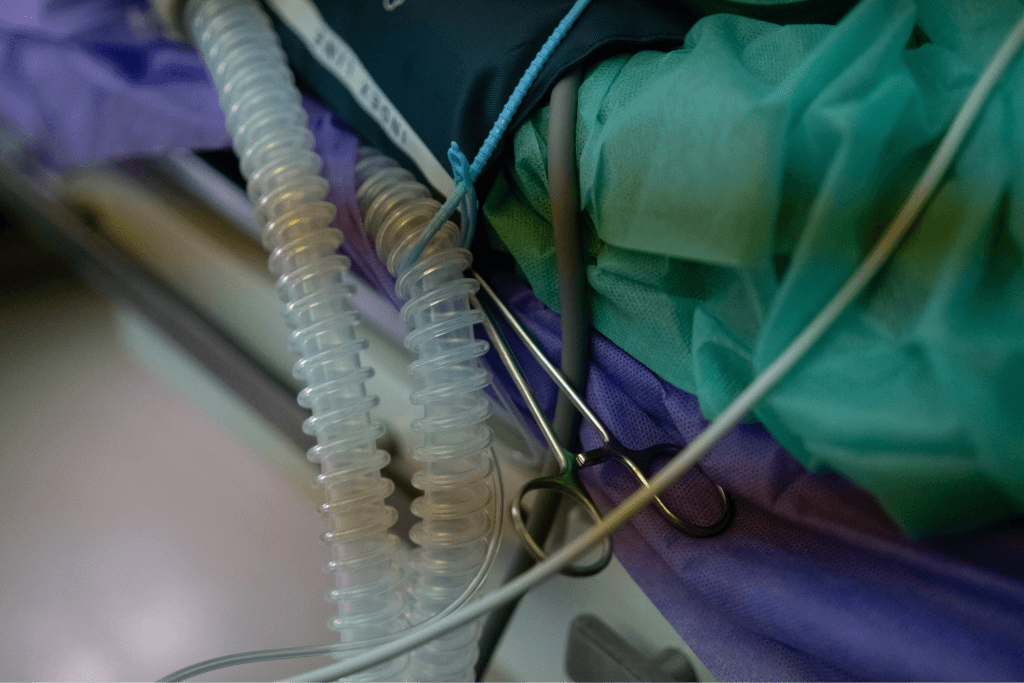

In preparation for the mission, the doctors meet regularly to discuss each patient and his or her surgical plan in detail, so that they have a full understanding of each case before the trip, and take all the necessary tools and supplies with them.

The second mission took place in Lviv in April 2023, and Illya took part in it. This time, the focus was only on active military with very complex facial injuries. The Face to Face organizers received over 100 applications, and selected 26 for surgery — only those who could not be helped by Ukrainian doctors.

“This time, the patients’ injuries were much more serious than last year,” says Ivanka. “They had a complete absence of a nose, injuries to the facial bones, complex defects of the lower and upper jaw, when a person cannot breathe, eat and communicate normally.

Ivanka recalls one of the patients who had no lower jaw and wrote to the doctors: “I really want to eat an apple.” The soldier had to write it down because he could not speak. After the surgery, he still cannot eat an apple — he still needs to have dental implants. But he can now speak, albeit not quite clearly, and has a normal face shape.

During the second mission, the doctors performed five highly complex surgeries, each of which lasted more than 15 hours. One of the patients had a bone transplanted from his leg to replace his upper jaw, along with arteries and veins. “We connected the bone vessels to the vessels in the neck to make sure everything would take root. This stitching is done under a microscope and takes two to three hours,” says Ivanka. “For the nose reconstruction surgery, they took a bone from the patient’s arm, and for another one, they took a muscle on the vascular pedicle.”

$1 million for 26 surgeries

The doctors who are part of the mission are oculoplastic surgeons (ophthalmologists who specialize in surgery of the eyelids, eyebrows, eye orbits, lacrimal system, forehead and cheeks), otolaryngologists who specialize in facial reconstructive surgery, and ENTs. Ivanka is a young specialist who assisted in the surgeries and was more involved in the organization of the mission and coordination on the ground.

“The anesthesiologists have never traveled with us, there are always Ukrainian doctors on site, and they are of really high level,” says Ivanka. “But the nurses come from the U.S. because these surgeries are very specific and new to Ukrainian medicine.”

In addition to helping patients, each of these missions aims to train Ukrainian doctors. They consulted with the Americans about specific cases and assisted during surgeries. For doctors who were not on site but also wanted to learn, there was an online broadcast of the surgeries, and it was watched by about 500 doctors. The broadcast involved moderators who commented on the process and explained all the surgeons’ actions.

“At the very beginning of the mission, American doctors held a master class for Ukrainian surgeons on stitching blood vessels under a microscope,” says Ivanka. “We bought pork ribs and chicken thighs and learned how to stitch blood vessels on them, to make small grafts.”

International charitable foundations and businesses help to finance the missions, while the instruments and autoclaves for sterilization remain in Ukrainian hospitals.

After the mission, Face to Face calculated that it would cost $1 million to perform the same 26 surgeries in America, including the purchase of instruments and supplies, logistics, and the work of doctors and their team. Face to Face is still calculating the cost of these operations in Ukraine. But it is already clear: it is at least ten times cheaper.

The trauma that is always in you

The last day of the Face to Face mission in Ukraine was April 28. It was on this day that Illya underwent his ninth surgery. Ivanka remembers the case well: after previous surgeries, Illya’s nose was scarred, and doctors tried to narrow it and reconstruct it.

“Everything worked out, even right after the surgery, with swelling, my nose started to look like a nose, not just an organ that performs some function,” says Illya. He spent almost another fortnight in the hospital, as doctors monitored his recovery and cartilage healing.

Now one can see a triangle on Illya’s nose, where the skin seems to be sewn on and is a little bit of a different color. However, a brighter future awaits as his nose gradually recovers, allowing for improved sense of smell, which is currently diminished.

“My nose started to look like a nose, not just an organ that performs some function”

Illya hopes to have only one more surgery ahead of him – on his eye. Last year, a new lens was put into his eye and silicone was injected – after that, Illya began to see a little. Now he can only see silhouettes with his injured eye.

During the upcoming surgery, the silicone will be removed from the eye and artificial air will be pumped in. At least that is how Illya understood these manipulations from the doctors’ words. He did not ask whether he would see better. Nor did he ask if anything would change in his appearance.

“I think that such an approach to appearance as Illya’s is correct,” says Ivanka Nebor. “We explained to each patient that the injury was so serious that it was impossible to restore the face to its original appearance. Yes, the nose will look like a nose, the jaw like a jaw. But it will not be the same as before. Patients need to realize this and accept their new look. Perhaps, they should prioritize their needs so that functionality, not appearance, comes first.”

Drawing from Ivanka’s experience over two missions, it is evident that military personnel tend to exhibit a greater sense of composure and restraint when discussing their injuries and the ensuing consequences, compared to civilians. However, this outward composure should not be misconstrued as an absence of inner trauma. They often grapple with these emotional wounds in solitude, carrying the burden silently.

“During the first mission, civilians showed a lot of emotion when talking to doctors,” Ivanka recalls. “They told us exactly how it happened to them – they were at home or at work when the missile struck. They told me how they experienced changes in their faces and how they perceived their appearance. The military are not very talkative. They only ask specific questions: what kind of surgery they will have, what kind of rehabilitation they need. They don’t want to talk about themselves, and we also try not to bring up these topics, so as not to aggravate their trauma with questions.”

After his latest eye surgery, Illya will go to Zhytomyr and serve in a rear-guard military unit. Almost a year ago, on August 6, he and Olha got married – in between treatments in Lviv and Poland. The couple had planned their wedding for this date even before the full-scale war broke out and decided not to change anything. When Illya talks about Olha and recalls their wedding, he looks happy.

“I want the war to end,” says Illya, “Then I will try to return to normal life. I dream about it – work, home, family. Before, I didn’t think about children, but now I really want them.”

“How come?”

“During the war, I realized that I had to think about the future. Every time I went on a combat mission, I thought: what will I leave behind if I die? There was no answer at the time. But I want something to remain. I want it to be children.”

Author: Tamara Balaeva

Photo: Vasyl Salyha

Translation: Bohuslav Romanenko, Oleh Pavliuk

Layout: Yuliia Vynohradska

Publication date: 05/27/2023

© 2023 All rights reserved.

Information agency ЛІГАБізнесІнформ

Projects is proudly powered by WordPress