Projects

Honoring the fallen

How the remains of fallen soldiers are searched for and brought home

Author: Tamara Balayeva

Illustrations: Anastasia Ivanova

Layout: Yuliia Vynohradska

At the end of winter 2023, Tetiana Dzey walked into the office of an investigator at the Main Department of the Ministry of Internal Affairs in Kyiv Oblast. She sat down at the computer and looked through 1,000 photos of the bodies of fallen soldiers. Tetiana was looking for a photo of her 22-year-old godson, Mykyta Belymenko. In March 2022, he was killed at a position in Mariupol. Tetiana still does not know where his body is and when it will return home.

Every month, the Ministry of Reintegration reports on the return of more than 100 bodies of soldiers to Ukraine from the temporarily occupied territories. From the beginning of the full-scale invasion to March 2023, the bodies of 1,426 defenders have been returned. However, thousands more relatives of the fallen have no one to bury and are waiting for the remains.

For over a year, relatives of victims have been painstakingly searching for the bodies of their loved ones who perished on the battlefield in Ukraine. LIGA.net investigated the lengthy process that relatives must endure as they wait for remains, why it can take so long to locate and retrieve bodies from active war zones, and the path a deceased’s body takes from the frontlines through identification and return to their family.

WHAT IS AZOV?

Back in 2005, Tetiana Dzey got a job as a nanny for two boys, Mykyta and Illya. Mykyta was six years old and Illya was ten days old. Almost immediately, she felt like a part of this family, and the family accepted her.

“The kids and I spent all the time together. I took care of little Illyusha, played with Mykyta, helped with homework, and took him to clubs,” says Tetiana.

She is a little over 50. She smokes an IQOS (heated tobacco and electronic cigarette product – ed.), drinks cappuccino, and, contrary to her story, there is some elusive lightness and even girlishness about her.

“The boys’ parents were seriously ill, so in a sense I immediately took on many of their mother’s functions. And then they asked me to become their godmother, and I agreed.”

In 2014, the boys’ parents died. At first, the brothers lived with their uncle, and four years later, when Mykyta was already an adult, Tetiana took custody of 13-year-old Illya. The woman’s husband and daughter did not mind. They began to live together in Boryspil.

“A year later, Illyusha entered the Bohun Military Lyceum, and Mykyta suddenly said he wanted to join Azov. I didn’t know what Azov was at the time,” Tetiana recalls and starts laughing as if she were reliving that conversation right now: “Azov? Isn’t this some kind of terrorist organization in America?”

Mykyta went to Mariupol for a medical examination, but failed. Doctors said he had a heart condition. “He called me crazed, asking me to take a cardiogram for him so that he could pass that medical examination,” Tetiana recalls.

“I refused, but then we went to Kyiv for an examination together. It turned out that there were no pathologies, just an atypical heart shape. My God, you should have seen Mykyta, how happy he was! He took that paper and started kissing it! He immediately went to Mariupol, and two days later he was told that he was being accepted to the Azov basic military training.

Mykyta went to Mariupol for a medical examination, but failed. Doctors said he had a heart condition. “He called me crazed, asking me to take a cardiogram for him so that he could pass that medical examination,” Tetiana recalls.

“I refused, but then we went to Kyiv for an examination together. It turned out that there were no pathologies, just an atypical heart shape. My God, you should have seen Mykyta, how happy he was! He took that paper and started kissing it! He immediately went to Mariupol, and two days later he was told that he was being accepted to the Azov basic military training.

The BMT is nine weeks of rigorous physical, psychologica,l and military training. The course is open to anyone who wants to join Azov. It is so difficult that on average 40% of the fighters do not complete the course, which means they do not join the brigade.

“There were 60 people in Mykyta’s course, and 24 dropped out by the end. But he passed!” Tetiana says with pride.

“When he died, a sergeant from the BMT told us how Mykyta had driven a splinter into his finger, and the finger had festered and his hand was swollen. But Mykyta still did not leave the course, because he would have had to wait two months for the next BMT.”

After the course, Mykyta sent Tetiana a photo of himself being awarded the Azov chevron, happily smiling.

After six months of service, he came home for his first leave and almost from the doorstep told Tetiana that he wanted to go to hot spots.

“I was very confused,” the woman says. “I thought for a long time about how to talk to him, and before I left, I asked him not to be the first to be called up for combat missions. I asked him to always remember Illyusha and make decisions with his brother in mind. Mykyta smiled strangely, and I did not understand what this smile meant. After his death, I received his combatant certificate and found out that he had already participated in hostilities.”

"MYKYTA HAS DIED"

In January 2022, Mykyta was supposed to go on another leave to Kyiv, but it was suddenly canceled. On February 24, the full-scale war broke out.

“Mykyta wrote that everything was fine in Mariupol, but he asked us to leave Boryspil as soon as possible,” Tetiana recalls. “He was very happy when we left for Uzhhorod and kept encouraging us: ‘Everything will be Ukraine’, ‘Don’t worry, we will stand our ground’, and his trademark ‘Hugging you tight and lifting a little’. I asked him some nonsense questions like whether he was fed or dressed warmly.”

After March 8, communication with Mykyta was interrupted. He did not respond to messages and did not read them. Tetiana was going crazy. At some point, she decided to search for chats on Telegram messenger using the word “Azov” and wrote the same thing everywhere: “I’m looking for my son”. “In one of these chats, I was asked for my son’s call sign and data. I wrote and they answered me: “He’s alive,” Tatiana recalls. “It was a chat of the Azov Patronage Service, and it was a lifesaver for me. If Mykyta didn’t write for two days, I would turn to that chat, get a message “Alive,” and I would feel better.”

The last time Mykyta called Tetiana was on March 26, and his voice was unexpectedly happy. “I heard that voice and said: ‘Mykyta, did they finally bring you food?’ He laughed and answered: ‘Weapons! They brought us weapons in a helicopter!’ I was stupid and thought he would rather have food. We talked very little. Finally, Mykyta said his ‘Hugging you tight and lifting a little’ and hung up.”

In early April, Tetiana and her family returned to Kyiv. Every few days she wrote to the Azov Patronage Service, asking about Mykyta, and every time she received an answer: “There is no connection with them. Be patient”.

“And then Illyusha went to visit his girlfriend in another city. I asked him to call me at any time if he received a text message from Mykyta,” says Tetiana. “At 12:30 a.m. on April 15, he called. I picked up the phone, thinking that it would be good news, and there was Illyusha shouting into the phone: “Mykyta has died.”

HOW MYKYTA DIED

Illya learned about his brother’s death on Instagram. Mykyta’s brother posted his photo with a black ribbon and the caption “The best are leaving. We will take revenge.” Tetiana wrote to this fellow soldier: “Is it true? Did you see the body? How did it happen?”

“He answered immediately,” says Tetiana. “He said that no one had seen the body. That the position Mykyta was in was fired at from a tank, and everyone who was there was considered dead. I wrote to the Azov Patronage Service and asked if this was true. Two days later, they called back and confirmed that it was.”

Tetiana started searching for Mykyta’s body immediately after his death. The morning after the news broke, she called a military friend from Boryspil and asked how to get the body out of Mariupol. The answer was harsh: “Pull yourself together and don’t think about it. It’s impossible now, even helicopters can’t get there. Don’t believe if someone tells you that you will bury your son soon.”

Tetiana heard about the imminent burial an hour after the conversation. The deputy mayor of Boryspil, to whom the woman had provided information about Mykyta, promised that the body would be returned in a week, two at the most. “For some reason, I believed her,” says Tetiana. “But we are still waiting for the body.”

In early June 2022, Tetiana received a certificate from the National Guard about Mykyta’s death. She immediately went to the investigator with this document. “I filed an application, and criminal proceedings were opened. A DNA sample was taken from Illyusha to identify the body when it was returned,” says Tetiana. “And then I was told that the case was transferred to the scene, to the Mariupol department of Interior Ministry, which is based in Dnipro, and that there was no communication with that department.”

In early June 2022, Tetiana received a certificate from the National Guard about Mykyta’s death. She immediately went to the investigator with this document. “I filed an application, and criminal proceedings were opened. A DNA sample was taken from Illyusha to identify the body when it was returned,” says Tetiana. “And then I was told that the case was transferred to the scene, to the Mariupol department of Interior Ministry, which is based in Dnipro, and that there was no communication with that department.”

The relatives of the other victims gave Tetiana the contacts of the Mariupol police on Telegram – cell phone numbers that she wrote to through messenger. “I received a reply: “Your case is under consideration. We do not disclose the course of investigative actions,'” she recalls.

“I wrote that Mykyta’s brothers-in-arms had returned from captivity and told me the new circumstances of his death. I received a reply: ‘Write the numbers of his fellow soldiers. If necessary, we will communicate with them’. I didn’t write the numbers because I didn’t know if it was really the Mariupol police or who they were.”

After the exchange in June 2022, when the first defenders of Mariupol were released from captivity, Tetiana was contacted by a fellow soldier of her godson. He said that he did not believe Mykyta was dead and asked her to appeal to the Red Cross to search for him in captivity. Tetiana was shocked – she had hope. The next morning, she took all the documents, and went to the Red Cross, where she filed an application.

“We talked a lot with Mykyta’s fellow soldier, Sasha, and then I went to visit them with my mother,” says Tetiana. “For some reason, all Azov soldiers immediately become my family. We still talk a lot, and after each exchange, Sasha tells me which of the released men might have known Mykyta.”

It was the same after the exchange in September 2022. Sasha sent Tetiana the contact of his fellow soldier and said that this person definitely had some information. “I was preparing for the call for three days. When I called, this soldier asked, ‘Are you ready to hear the truth?’ I answered that I was ready to hear only the truth. Then he said that Mykyta was definitely dead. And he told me how it happened.”

Tetiana and I are sitting on the summer terrace at McDonald’s, and she points to the yellow cappuccino cups: there were two positions. One was occupied by Mykyta and five other people – Tetiana puts one cup down. In the other, about 800 meters away, there were a few more soldiers – Tetiana puts down the second cup.

“Mykyta received a radio message: ‘We are being blasted! We need help’. Out of the six of them, two ran – our Mykyta and the 38-year-old ‘Kobzar’. Mykyta could have stayed, but he ran, you know,” says Tetiana, crying for the first time during the conversation.

“Everyone was killed at the position they ran to. It happened on April 14, 2022, at 4:52 am. Not a single body was recovered. Kobzar’s wife is still waiting for him. She saw him on a video from captivity – she thought so, although everyone says it’s not him. I understand her, I would have thought so too.”

From that conversation, Tetiana learned that after the shelling of the position, the command did not give the order to go and see if there were any wounded. “Other soldiers also confirmed this to me,” says Tetiana, lighting a new IQOS stick. “I understand it was dangerous. The guys could have died if they had left. I don’t have any resentment, and I didn’t have any even back then.”

THE PATH OF THE BODY

According to the Ministry of Reintegration, from the beginning of the full-scale invasion to March 2023, the bodies of 1,426 defenders were returned to Ukraine from the temporarily occupied territories. The Azov Patronage Service says that as of now, a little less than half of the brigade’s dead have been buried.

The path that the bodies of the soldiers killed in Mariupol have taken and are still taking is somewhat different from that of other hotspots.

“Azovstal had mobile morgues – not in bunkers, but on the grounds of the plant,” explains Natalka Bahriy from Azov’s Patronage Service.

“If they managed to recover the bodies from the positions, they were put there. Then a rocket hit the mortuary, and the bodies were moved to the lower bunkers, to the hangar, where it was cool.”

From the beginning of the full-scale invasion to March 2023, the bodies of 1,426 defenders were returned to Ukraine from the temporarily occupied territories

In Mariupol, Azov had a fairly clear system of notifications about the deaths of soldiers: “People who were in the positions saw with their own eyes the hits to other positions, and they knew who was there. They passed the information on to their commander, who passed it on to the regimental commander (Azov became a National Guard brigade only in February 2023 – Liga.net). Everything was recorded, we were given the lists, and we notified our relatives,” Natalka recalls.

She adds that back then, relatives were told that their loved one was dead, even if the body could not be retrieved and the soldier was officially considered missing. Now, this is no longer the case: if a soldier is listed as missing in action, this is what relatives are told – until there is an official notification of death.

The bodies of those killed in Mariupol were stored in mobile morgues at Azovstal until mid-May 2022, when the military left the plant as captives. The bodies were then taken by the Russians, and the first exchange took place in June.

“Speaking about those killed in the war in general, not in Mariupol, it happens that senior officers on both sides agree to exchange bodies on the spot, and it happens instantly,” says Natalka.

“This is an old practice, it has been done for many wars. But when there are active hostilities, it is impossible to take a body from the positions for weeks – for example, in Bakhmut. Or it is not possible to agree on an instant exchange on the battlefield, and then it is agreed upon at the official level, which can take several months.”

The Armed Forces humanitarian mission On the Shield transports the bodies to the settlements where they will be buried. It is subordinated to the Central Department of Civil-Military Cooperation of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Ukraine. This means that the mission includes both military and civilians. The military members of On the Shield refuse to comment for the press.

Civilians who carry bodies from the frontline areas are based in different regions of Ukraine and make trips with different frequencies. In Rivne, Oleksandr Hrebeniuk is involved. He has been volunteering since 2014 – first he drove vehicles to the front, then he was involved in rehabilitation of veterans and assistance in legal matters, and initiated the opening of the Veterans’ House in Rivne.

“When the full-scale war started, I wanted to join the army, but they wouldn’t let me with my illnesses,” says Oleksandr. “Almost from the first days of the invasion, relatives of the dead started contacting me and asking me to help them find the bodies. So we quickly found sponsors, bought two mobile morgues, got diesel, and started driving around to find the bodies. I think we made our first trip on March 8, 2022.”

Since then, Oleksandr and his team have transported more than 1,000 bodies of fallen soldiers from the frontline areas. Now they make trips twice a week, and in one day they can visit up to 20 morgues in frontline settlements from Kharkiv to Zaporizhzhya oblasts.

“Each brigade has a representative of civil-military cooperation. He is responsible for bringing the body from the battlefield to the first morgue,” explains Oleksandr. “We pick up the body there and take it to the morgue in the settlement where it will be buried. On a single day, collecting bodies from morgues in different localities can last from 8 a.m. to 11 p.m.”

“We quickly found sponsors, bought two mobile morgues, got diesel, and started driving around to find the bodies”

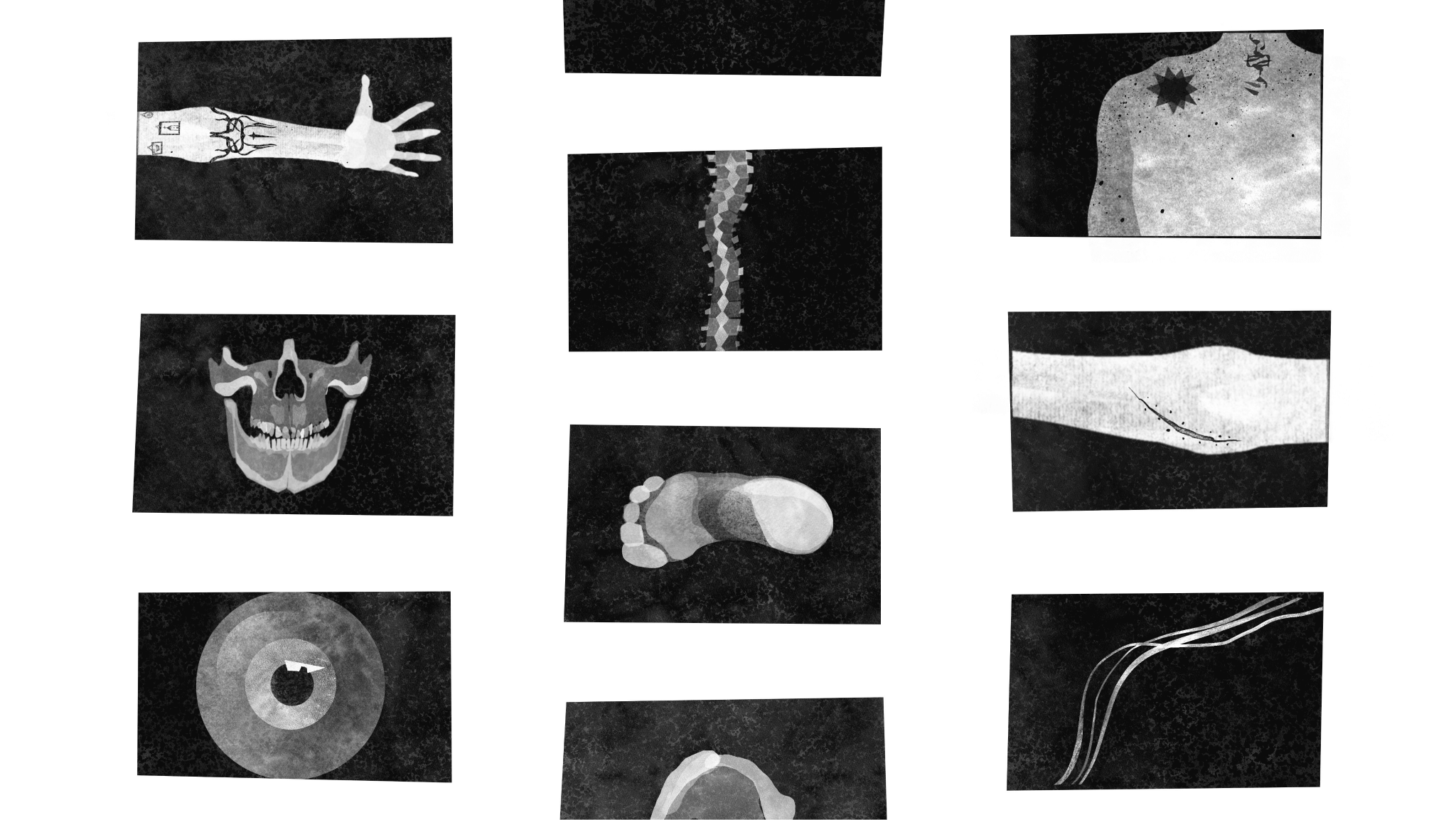

Azov’s patronage service cooperates with On the Shield in returning bodies. “They bring the bodies to Kyiv, we help to receive them, examine them, and take photos,” says Natalka Bahriy. “Before that, we ask the relatives for photos of the tattoos of the victims so that those who have them can be identified visually. If this is not possible, the bodies are subjected to DNA testing.”

According to Natalka, more than half of the defenders of Mariupol are not buried because of the lack of DNA matches with close relatives.

The fact is that only one organization in Ukraine has the right to analyze DNA matches – the State Scientific Research Forensic Center of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Ukraine (SSRFC). But it analyzes not only the data of those who died or went missing in the war, but also the DNA data of all those involved in criminal and civil proceedings, including murder cases, paternity cases, and others. The workload on the system is high, so it takes a long time to get the results of the examination in each case.

“The research is ongoing, and we have no complaints about the work of the SSRFC,” says Natalka Bahriy. “But the final result requires two DNA matches – a preliminary and a final one, which already shows the percentage. Families can wait for it for six, seven, eight months.”

Only one organization in Ukraine has the right to analyze DNA matches

Another problem is that the bodies that come in for the exchanges are in very poor condition – sometimes they are just pieces of bones. It is difficult to extract DNA from them, sometimes you have to do it twice or even three times, and this further delays the identification process.

“And sometimes it happens that parents have taken a DNA test once, and the results show a kinship with the deceased. But they don’t want to believe that their son is dead, so they retest again. They receive confirmation again, but still refuse to believe and do not take the body,” says Natalka. “This also burdens the DNA research system and affects the speed.”

While the results of the examination are not yet available, the bodies are in a state of deep freeze in mobile morgues in the settlement where they were brought.

This means that the body of Tetiana Dzey’s godson Mykyta, like many other fallen soldiers, may have already been returned to Ukraine. But his DNA has not yet been processed.

1,500 PHOTOS OF THE BODIES’ REMAINS

Relatives of fallen soldiers unite, exchange information, help each other and search for the bodies of their loved ones together. Tetiana Dzey is a member of the community of relatives of fallen Azov soldiers created by the brigade’s Patronage Service.

“I met other parents there who were also looking for the bodies of their sons,” says Tetiana. “We started searching together. Last fall, we found the contacts of the morgue workers in Dnipro, texted them the data of the dead guys, sent them photos and asked if they had any. I know a few parents who found their sons’ bodies this way. I did not. And now, as far as I know, morgues no longer contact the relatives of the dead.”

Oleksandr Hrebenyuk from Rivne and other volunteers who transport bodies from frontline cities are now mediating between morgues and the families of the dead. “I have a list of 195 people who died in the last two or three months of the counteroffensive. Their relatives contacted me, sent me their data, distinct features and photos, and asked me to find the bodies,” says Oleksandr. “When I come to the Dnipro morgue, I always sit down and look at the new bodies that have been brought there. If something looks familiar, I start digging through my phone and looking for a photo match.”

If Oleksandr thinks that the body looks like the one in his requests, he writes or calls the family, and they start an “identification” over the phone – Oleksandr asks about tattoos, scars, moles, and anything else that might help identify.

“Previously, morgues communicated directly with the relatives of the deceased”

“There have been cases when, after such conversations, relatives came to the morgue and identified their deceased,” says Oleksandr. “And sometimes, for example, a guy has only his 82-year-old mother. How will she come from Rivne for the identification and what condition will she be in afterwards? Then the relatives write a statement that they will not have any claims against us, and on the basis of this statement I make an identification protocol and bring the body. This whole process of remote identification takes a lot of time, especially if the body has no face. We can’t make a mistake and then bring the body back — it’s a waste of time and diesel. That’s why we check everything carefully.”

At the end of last winter, Azov’s Patronage Service agreed with the Kyiv Oblast Investigation Department and the Shevchenkivskyi Department of the Kyiv Interior Ministry to allow the relatives of the victims to view photos of the bodies that were brought to the capital and the region.

“The parents did not believe that the bodies were in a very bad condition and it was often impossible to identify them visually, so they just had to wait for DNA,” says Natalka Bahriy. “So my colleague simply negotiated with the investigators using words and personal relationships. The relatives looked at the photos and realized the full picture.”

Tetiana also made an appointment to see the photos at the police station. There were about 1,500 photos of mutilated bodies. “Other parents, who had already gone to the identification before me, called me to reassure me,” Tetiana recalls. “They said that there was nothing particularly scary in those photos, but that I should be prepared to see worms and stuff. I was kind of ready.”

Mykyta had no tattoos, so Tetiana could only recognize him by his amulet, which he never took off – an iron National Guard badge, an electronic watch, and a specific bite.

“We looked at the first 1,000 photos on a laptop in the office for five hours,” Tetiana recalls. “I took some photos on my phone to look at them at home — where I thought Mykyta’s teeth looked like his. I took it somehow normally. A few days later, we went to another room to look at 500 more photos, and around the eighth photo, I had a hysterical fit. I saw a hand with an electronic watch, and I thought it was Mykyta’s watch. The investigator came running and started to calm me down: “It’s not him. Look, the victim was wearing a Casio watch, but you have a different brand. It’s not him.” My body was no longer obeying, but I finished looking at all the photos. Mykyta was definitely not in them.”

TETIANA'S DREAM

Every night before going to bed, Tetiana likes to spend some time alone. She locks herself in her room, opens Telegram, and starts looking through chats and channels about the search for the dead, missing, and captives. Ukrainian ones and those where Russians post photos. She zooms in and inspects each photo carefully. If she thinks the person in the photo looks like Mykyta, she sends it to Illya. Every time she gets a response: “No, it’s not him.”

“In the winter, I had a dream,” says Tetiana. “As if I was coming home, taking off one boot and hearing a man’s voice: ‘Look who I brought you’. I take off my other boot, go into the kitchen, and there sits Mykyta, wearing the T-shirt I gave him, his sneakers, in the place where he always sat. I run up to him, grab his shoulders, and start shouting: ‘Mykyta, where were you? Where were you? I cried so much! Where were you?’ And he hugs me and says: ‘Oh, Tanya, where have I been? I even went through Boryspil, but I couldn’t get out. But now everything will be fine, I’m here’.”

Tetiana remembered the dream in detail and tried to analyze Mykyta’s words in it. “The phrase ‘I even went through Boryspil, but I couldn’t get out’, was particularly troubling to me,” she says. “I thought that maybe he had already been brought in a mobile morgue and was somewhere here. That’s why I went to look at those photos at the police station and have been looking for him ever since. But I haven’t found him yet.”

When the National Military Memorial Cemetery is opened in Kyiv, there will be an alley for burying empty coffins – those whose bodies have not yet been found, but whose loved ones need to come somewhere and have a physical place to grieve. Tetiana is looking forward to it. In the meantime, she has a flag with Mykyta’s call sign on the Maidan, and she goes to talk to her godson there.

Projects is proudly powered by WordPress