Projects

Spider-Man

Who and how created a network of torture chambers in occupied Kherson Oblast

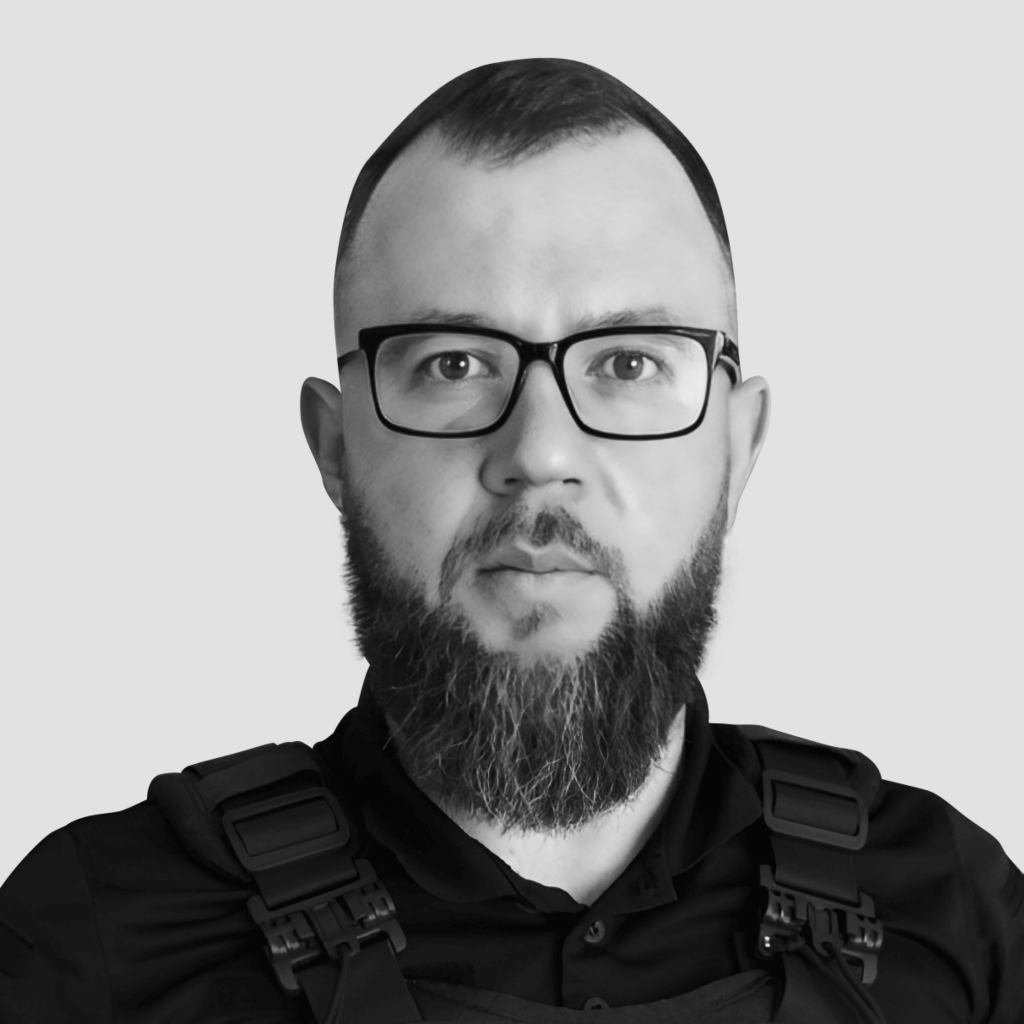

Author: Dmytro Fionik

Illustrations: Anastasia Ivanova

Layout: Yuliia Vynohradska

Ahead of the anniversary of the liberation of Kherson city, LIGA.net investigated how the system of terror was built in the occupied region and who was behind it.

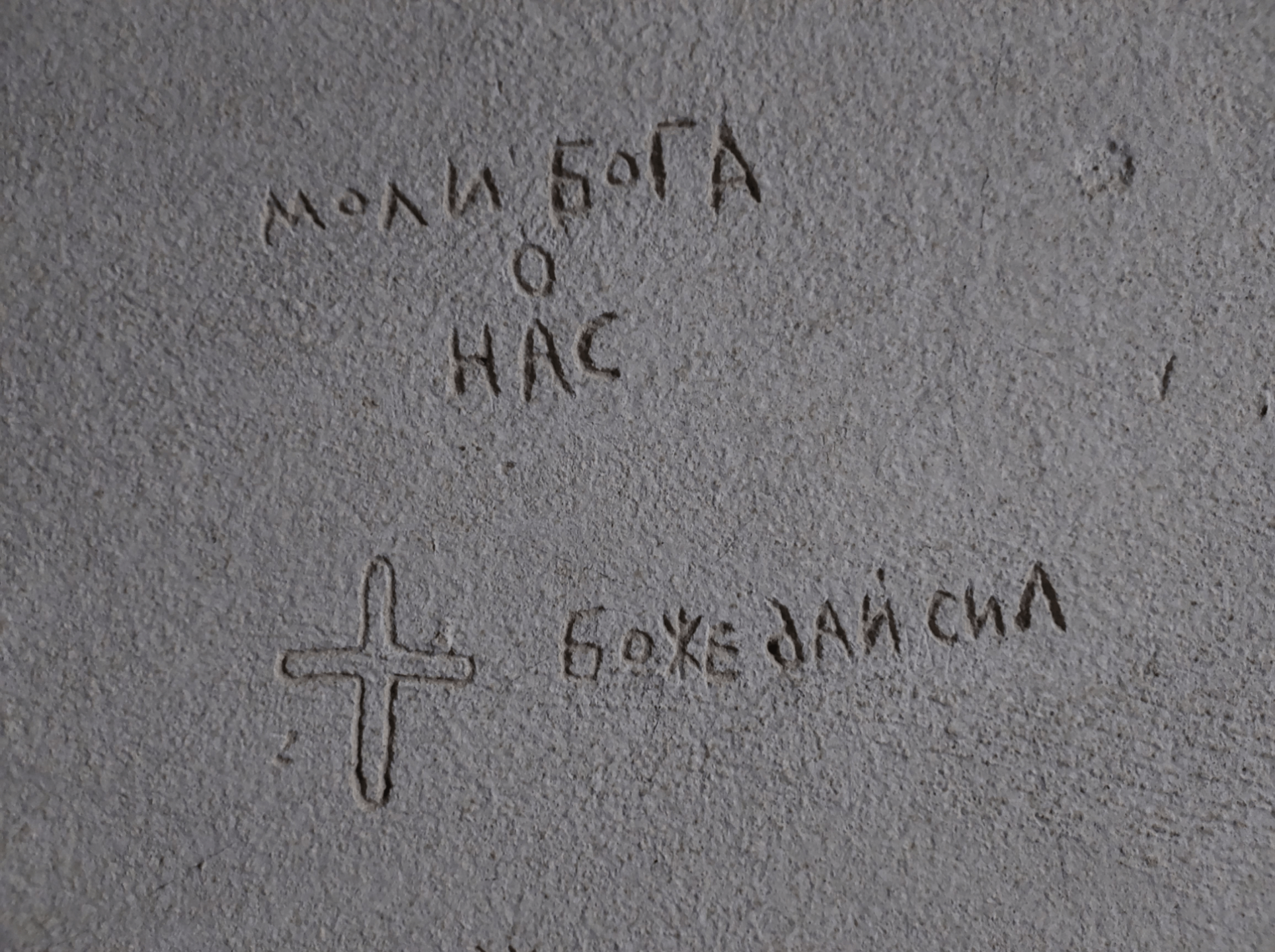

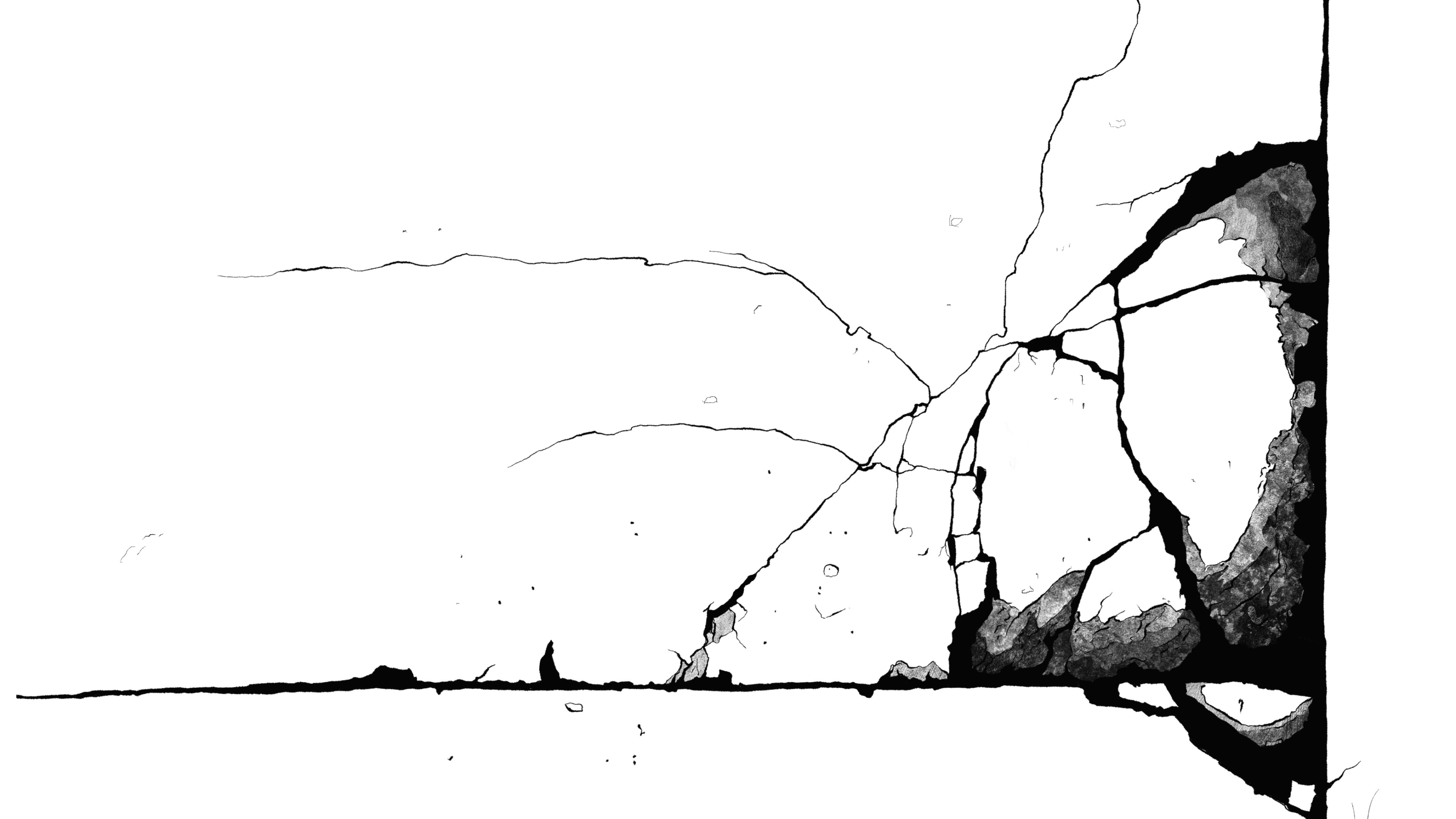

Kherson, Pylyp Orlyk Street, the basement of a large office building. The cobwebs are everywhere: on the ceiling, on the walls, and on the pipes. In peacetime, people entered this basement only a few times a year to connect something or adjust the heating system. All the rest of the time, spiders ruled the place.

In April 2022, the building housed the so-called GSB [‘gosudarstvennaya sluzhba bezopasnosti’, ‘state security service’]. In the basement, the temporary owners set up a torture chamber. The newly created body was headed by the former head of the Yanukovych-era SBU (Security Service of Ukraine), Oleksandr Yakymenko. This 58-year-old man personally took part in the torture.

When the occupiers fled the city, they burned various objects in the basement corridor to destroy the traces of their crimes. Thus, the gray realm of spiders was covered with black soot. The spiders fled or died, but the webs remained – black patterns were forever embedded in all surfaces.

Neither investigators nor victims refer to such places as prisons. After all, a prison is an institution whose existence is regulated by certain rules. In the Kherson basements, arbitrariness, not rules, reigned supreme. Here, prisoners were driven to madness and killed. Sometimes just for fun. That is why the word “torture chamber” has become an almost legal term.

According to the Kherson Oblast Prosecutor’s Office, about 1,500 Ukrainian citizens were abducted during the occupation. And this is a very cautious estimate, as the exact number of prisoners the occupiers took with them is unknown. Their fate is also unknown.

The investigation of these crimes has been going on for a year. Investigators of the SBU, the National Police and the State Bureau of Investigation managed to reconstruct the overall picture of terror in Kherson Oblast. Law enforcers established more than ten former torture chambers in the de-occupied part of the region. Five of them were located in Kherson proper.

Investigators from the Security Service of Ukraine and the Main Directorate of the National Police in Kherson Oblast told a LIGA.net correspondent how and when this or that “place of detention” was created. Today, we know the names of dozens of Kherson torturers, as well as the name of the alleged architect of the “black web” system. And it was not Yakymenko, by the way.

The Invisible Colonel

Ihor Demianiuk, Head of the Investigation Department of the Main Directorate of the National Police in Kherson Oblast, is in charge of investigating crimes committed in two “places of detention”: the basement of the Main Directorate of the National Police and the premises of the temporary detention center. The police officer states: “In all torture chambers, the Federal Security Service (FSB) is the leading agency.”

The SBU officers in Kherson Oblast, who are in charge of another torture chamber, the already mentioned GSB, call out the name and position of the “head of the senior management”. This is FSB Colonel Sergei Sinitsyn, an employee of the third bureau of the ninth directorate of the Department for Operational Information.

This name means a lot to law enforcement, but it may escape the attention of historians and political scientists who will someday write monographs on how the occupation authorities were organized. After all, Sinitsyn himself did not apply for any “ministerial” positions, did not sign any “state” documents, and did not appear at any public events.

His subordinates referred to him by his call sign, “Sabir.” Sabir seems to have left no signature, no living memory among locals. It is not known where he lived, in which cafe he ate, or how he spent his free time. But we do know something about him after SBU investigators shared information about Sabir with LIGA.net.

Personal inforrmation: Sergey Viktorovich Sinitsyn, 48 years old, born in the village of Chamzinka, Mordovian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, registered in Moscow in the residential complex “Stolichnye Polyany”. While in Kherson, he was in charge of the FSB unit VOG-8. VOG is a Russian abbreviation for “temporary operational group”.

Distinct features: smallpox marks on his face. An ordinary, inclined to obesity man, resembling a mid-level bureaucrat. This is, in principle, what he looked like in his natural environment – on the streets of Moscow. In Kherson, Sinitsyn turned into “Sabir” and became the shadowy master of a region with a population of more than one million and a territory the size of a small European country.

In Kherson, Sinitsyn turned into “Sabir” and became the shadowy master of a region with a population of more than one million and a territory the size of a small European country

The charges reveal that the colonel received unlimited powers from the Moscow leadership: “The tasks assigned by the FSB to S.V. Sinitsyn included the creation and control of the activities of the occupation authorities, including criminal organizations under the guise of law enforcement agencies, the introduction of currency circulation, the use of the taxation system, the registration and activities of business entities, authorities and local self-government, the introduction of the system of legislation of the Russian Federation, etc.”.

In other words, the colonel’s goal was to turn Kherson Oblast (and possibly part of Zaporizhzhya Oblast) into the Russian Federation. It is not only about the repressive agencies, but also about the administrative and financial block of the occupation authorities of Kherson Oblast.

Russian troops entered the city on March 1. According to the charges, Sinitsyn arrived in Kherson “no later than March 10, 2022”. The SBU clarified: “On March 5, Sabir was already here. He was traveling with security in an SUV without license plates. And he may have managed to arrange a workplace in the Kherson Oblast State Administration or in another administrative building.

In those days, many thousands of anti-occupation rallies regularly gathered on central Freedom Square. On March 5, 2022, Sabir could see an armored personnel carrier with the letter Z moving through the crowd from his window. Someone from Kherson stuck a poster “Kherson is Ukraine” on the APC. Suddenly, a man with a Ukrainian flag jumped out of the crowd and onto the armored vehicle. The APC continued to move down Ushakov Avenue…

Sabir sees a sad picture: the whole of Kherson is covered in yellow and blue ribbons. In the city center he hears: “Putin is a f..ker”, “Glory to Ukraine” and “Kherson is Ukraine”. Ukrainian flags are flying over the city council and some state institutions. How to turn this yellow and blue sea into the Russian Federation?

Ukrainian flags are flying over the city council and some state institutions. How to turn this yellow and blue sea into the Russian Federation?

There is no doubt that FSB agents were taking photos and videos of the protests. Some of the residents of Kherson who later found themselves in torture chambers attended these rallies. If we assume that about 10,000 people gathered at the protests, and more than a thousand were put through the torture chambers, we can conclude that eventually every tenth protester ended up in the basement.

The man who rode with the Ukrainian flag on an enemy armored personnel carrier managed to disappear from the FSB’s sight. He turned out to be Vladyslav Pastukhov, an employee of the Kherson Criminal Investigation Department. He moved to the territory controlled by Ukraine and continued to fight the occupiers.

But Sabir continued his work. The FSB’s focus at that time was, of course, pro-Ukrainian activists, journalists, and religious figures. They also targeted all former military personnel, Anti-Terrorist Operation participants, and law enforcement officers.

Prosecutor of the Kherson Oblast Prosecutor’s Office Oleksiy Butenko, who receives all information related to FSB crimes in occupied Kherson, notes that Sinitsyn’s characteristic feature is his sociability, his ability to quickly adapt to any interlocutor. Sabir simply “talked” to people. He was an invisible man who was everywhere and nowhere at the same time.

The first torture chambers

A wave of detentions and searches swept through the city. The primary task of the FSB is to establish the whereabouts of all Ukrainian citizens who could potentially provide forceful or ideological resistance. The next step is to lure these people to their side or “neutralize” them.

Probably, in the first days of the occupation, FSB representatives still had the illusion that the process of turning Kherson Oblast into Russia would resemble the annexation of Crimea. Eight years ago, a significant part of the law enforcement personnel of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea sided with the enemy. But in Kherson, the occupiers faced resistance at every turn.

The first torture chamber in the city appeared on March 9 in the premises of the temporary detention facility. The Russians had to seize the facility with the help of the National Guard (Rosgvardia). The head of the Federal Service of the Rosgvardia in Rostov Oblast, Lieutenant Colonel Aleksandr Naumenko, personally negotiated with the staff of the temporary detention facility, offering them to keep their jobs.

The temporary detention facility became the largest torture chamber in Kherson. According to the National Police, about 400 Ukrainian citizens had gone through it

When talking about this episode, investigator Ihor Demianiuk pauses. When asked if any of the detention center staff accepted the occupier’s offer, Demianiuk answers: “No one agreed!”

Later, the Rosgvardia under the command of Aleksandr Naumenko also seized the building of the police department. The basement of this institution also used to be a detention center. But in recent years, these cells were considered unsuitable for holding people and were not used for their intended purpose.

Both torture chambers were quickly filled to capacity. The temporary detention facility became the largest torture chamber in Kherson. According to the National Police, about 400 Ukrainian citizens passed through it. The National Police building was smaller, holding about 60 prisoners.

Ihor Demyanchuk notes that there was a conditional specialization of these institutions. The cells of the temporary detention facility were filled with relatives of servicemen, people who participated in rallies, whose phones were found to contain compromising information… In contrast, in the National Police building they detained and tortured mostly territorial defense fighters, ATO members, local politicians and other “dangerous” persons.

However, this was a conditional division. Politicians or activists could end up in any basement. For example, the mayor of Kherson, Ihor Kolykhayev, was held in the temporary detention facility for some time. Then the captive was taken away. Another former mayor of Kherson, a patriotic Volodymyr Mykolayenko, was taken to the National Police building. His fate is still unknown.

The architecture of the web

At the beginning of April, at least two torture chambers were already operating at full capacity – almost every active Kherson resident had a friend who was “in the basement” at that time. But mass protests in Kherson continued. The rallies became smaller. But the occupiers only dared to remove Ukrainian flags from local councils on April 25.

In the evening of that day, Russian soldiers led by the commandant of Kherson Oblast, Colonel Viktor Bedryk, entered the city council building. The occupiers changed the guard, removed Ukrainian symbols and held a meeting.

At the meeting, Commandant Bedryk introduced the new “head of the Kherson administration” – an unknown Oleksandr Kobets. On the same evening, Volodymyr Saldo was proclaimed the occupation mayor.

Of these three characters, only collaborator Saldo, the mayor of Kherson from 2002 to 2012, needs no introduction. Who, after the so-called referendum, will become the “governor of Kherson Oblast.” But from a purely forensic point of view, Commandant Bedryk and the “jack-in-the-box” Kobets are also interesting figures.

According to the charges, Russian military officer Viktor Bedryk arranged a separate torture chamber in the commandant’s office. The commandant’s office was located in the building of the Court of Appeal, where the layout of the building itself provides for cells for defendants. During the occupation, people were tortured with electric shocks and beaten to death in these cells.

The 64-year-old Oleksandr Kobets, whom Bedryk revealed to the world, was clearly a creature of the FSB, i.e. Sinitsyn-Sabir. Until 1991, Kobets worked in the KGB, and later in various positions in the SBU. He was dismissed with the rank of colonel in 2006. In retirement, he worked part-time as a head of security services in various commercial entities. In March 2022, he left Kyiv for Europe and ended up in Kherson a month later.

In mid- to late April, another batch of “law enforcement veterans” arrived in the city at Sinitsyn’s invitation

At that time, Sinitsyn-Sabir worked as a recruitment agency. He invited all the former law enforcement retirees he could reach to meetings. These meetings began with the words: “Valery Valerievich recommended you to me”. Sinitsyn would just talk to people…

Valeriy Valeriyovych was well known in Kherson. This is the member of the regional council Valeriy Litvin, a former head of the police in Kherson Oblast. During the occupation, he actually became the FSB’s chief advisor on personnel issues. But despite his mediation and terrifying rumors about where those who did not agree to cooperate ended up, it was not possible to fill the staffing of the newly created repressive bodies with local personnel.

In mid- to late April, another batch of “law enforcement veterans” arrived in the city at Sinitsyn’s invitation. In particular, the former head of a Ministry of Internal Affairs department in Cherkasy Oblast, 52-year-old Volodymyr Lipandin, and the former head of the Security Service of Ukraine, 58-year-old Oleksandr Yakymenko, who were wanted for Maidan-related crimes, arrived from Crimea. The latter arrived with an entourage of old friends – first-wave collaborators from Crimea and Donbas.

Criminal charges against Sinitsyn, Lipandin and Yakymenko are merging into one spy detective case.

According to the investigation, “in an unspecified manner and at an unspecified time, but no later than April 29, 2022”, Sinitsyn informed Lipandin and several other persons of his intention to create a criminal organization called “the Main Department of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Kherson Oblast”.

And here is a quote from another criminal case: “Implementing the pre-planned criminal intent, in April-May 2022 (a more precise time was not established during the pre-trial investigation), Oleksandr Hryhorovych Yakymenko (…) headed the so-called ‘State Security Service of Kherson Oblast’ and began to implement the previously planned criminal intent as the commander of an illegal armed formation.”

The GSB was created as an analog of the “DPR MGB” and was in fact a kind of FSB subcontractor for dirty deeds

The bottom line: Sinitsyn “entrusted” the so-called “Main Directorate of the Ministry of Internal Affairs” to Lipandin, and the GSB to Yakymenko. The GSB was created as an analog of the “DPR MGB” (the so-called “Ministry of State Security of Donetsk People’s Republic”) and was in fact a kind of FSB subcontractor for dirty deeds. So in May 2022, the “black web network” was built. But the main spider remained in the shadows.

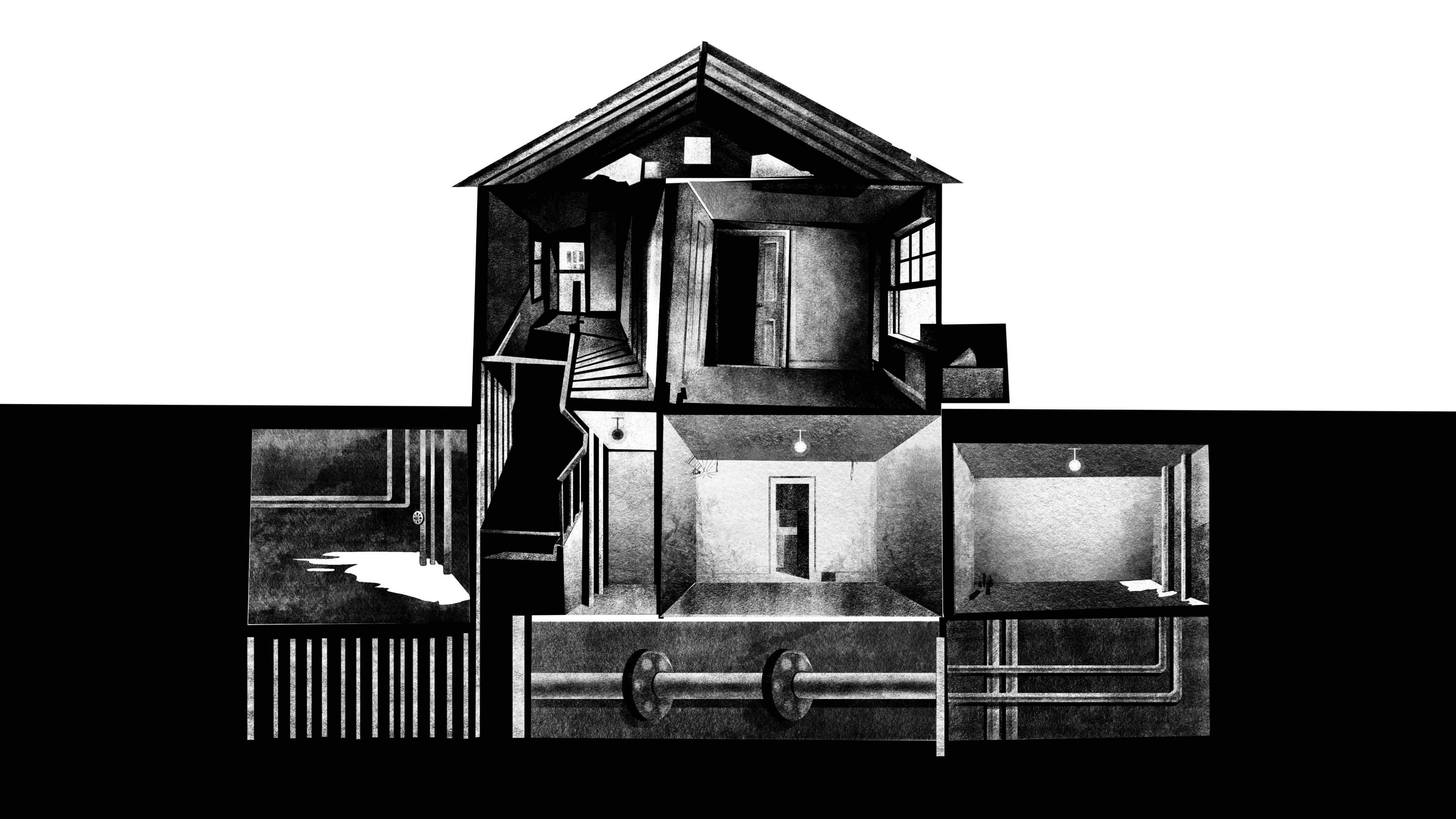

In late May and early June, four large torture chambers were already operating in the city. In the temporary detention facility, in the building of the Main Directorate of the National Police, in the building of the Court of Appeal and, of course, in the basement of the newly created GSB.

Not only resistance members, former law enforcement officers, or public opinion leaders were caught in the black net. Anyone could find themselves in a torture chamber.

Cell number six

Faina, a senior nurse at a Kherson hospital, has never been a political activist. She is an elderly, dark-haired woman with wise eyes. She speaks Russian with a slight Armenian accent. If any of her friends or colleagues had been told that Faina would be imprisoned as an accomplice of the “Ukrainian Nazis,” no one would have believed them.

But she got caught. For her son, a volunteer who helped the locals evacuate to the territory controlled by Ukraine. A couple of months before the so-called “referendum,” repressions against the population intensified. In particular, volunteer transporters, whose activities had previously been turned a blind eye to, were being rounded up.

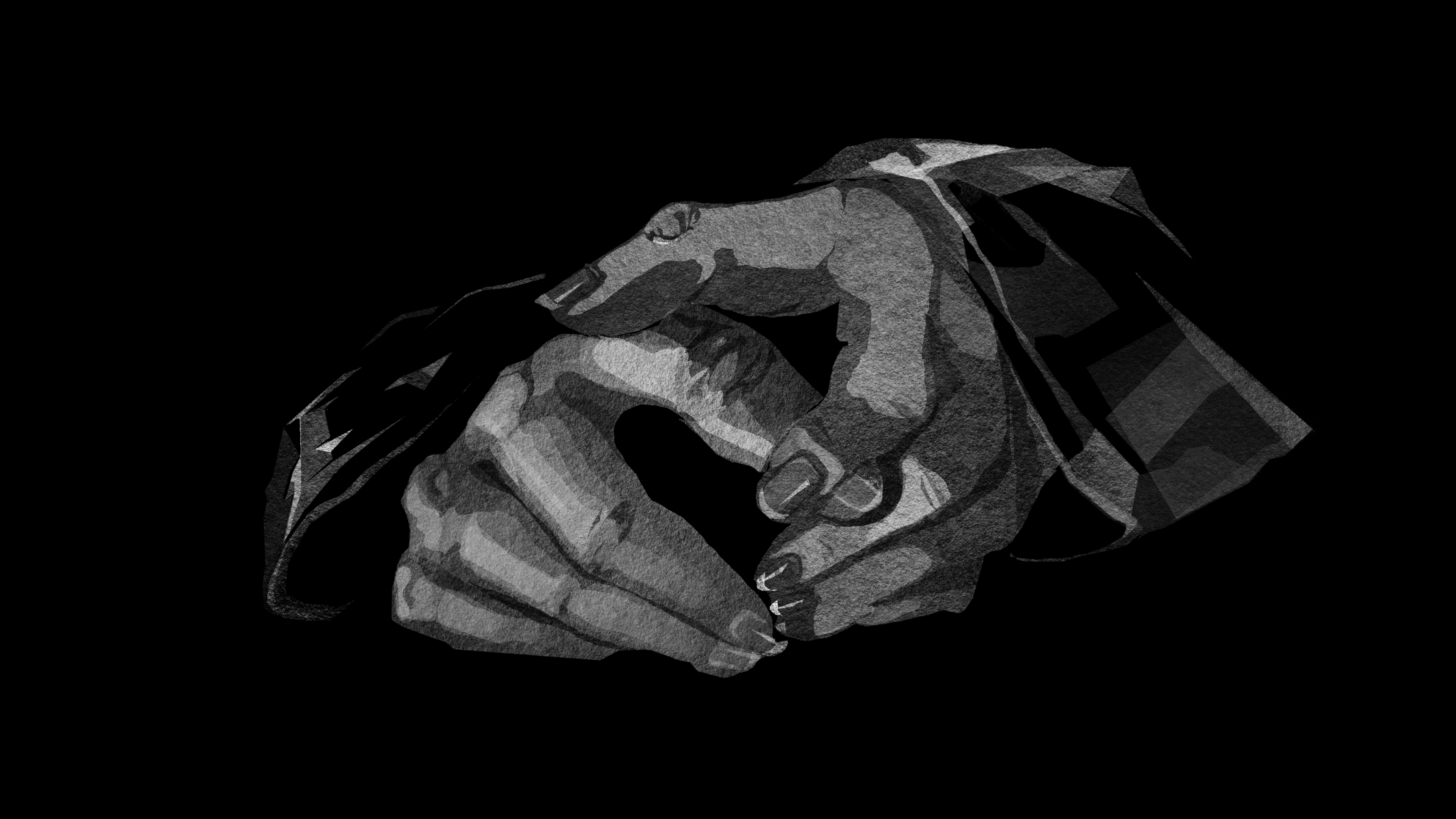

In fact, Faina was taken hostage. The occupation authorities demanded that she call her son and force him to surrender to them. Hostage-taking was one of the most common methods of “denazification” of Kherson.

There were other hostages in the same cell (number six) in the temporary detention facility building. English teacher Olha was imprisoned for her brother, a military officer. Svitlana, a scientist, was held for her husband, a fish inspector, whom the occupiers suspected of having ties to partisans. Another cellmate was Natalia, a volunteer.

Hostage-taking was one of the most common methods of “denazification” of Kherson

The story of women’s cell number six and the names of the women are known to us thanks to Kherson journalist Anzhela Slobodian, who was imprisoned for her professional activities. In the occupied city, she continued to shoot videos on her iPhone, which later became the basis of the documentary film “Incursion“. The journalist spent 31 days in the detention center.

For other women, Faina was in a sense a salvation. The fact is that many of the abducted people had no contact with the outside world so their relatives and friends considered them missing. But Faina’s daughter knew about her mother’s whereabouts. She could hand over hygiene items and food.

Anzhela was kidnapped right on the street. “I didn’t have any necessary things, such as spare underwear… And Faina gave me underwear,” she can hardly hold back her tears as she recounts what happened.

Thanks to the parcels from Rita, Faina’s daughter, she even had candy in the cell. Faina herself suffered from diabetes and almost never ate sweets.

The women in cell six were not subjected to sexualized violence, beatings, or any ‘special’ torture. But men were beaten – right outside the cell door.

“We heard it all the time, it was impossible to stand it,” says Anzhela, “we even heard the Russian Guard servicemen, Chechens, handing out condoms to the prisoners who had been there before the invasion, so that they could rape our guys…”

Faina listened to the unbearable screams outside the door. Sometimes she thought it was her son screaming. The thought that her son had already been captured and was being tortured tormented her around the clock, and she hardly slept. She kept repeating, “My Liova, my Liova…” At some point, she felt sick.

“Her face changed, her facial expressions became unusual, her limbs were cold…” recalls Angela. “We started shouting that we needed a doctor. The wardens found a doctor among the prisoners and brought him. He measured her blood pressure, which didn’t seem critical. I looked him in the eye, and we understood each other. He told the wardens, ‘It’s bad, it’s bad, it’s a pre-heart attack…”

Faina listened to the unbearable screams outside the door. Sometimes she thought it was her son screaming

The Russian guardsmen did not need an extra corpse. Faina was taken to the hospital. She was not diagnosed with preinfarction angina, and, after a while, sent back home. By the way, the Russian occupiers never caught her son. Anzhela and Faina’s other cellmates believed that her story had a happy ending.

“When I was released, I decided to visit Faina,” Anzhela recalls. “I knew her address; we memorised addresses so that the one who was released could give information about the other girls to their relatives.”

But Anzhela was too late. Faina died two weeks after she was released. “Her real name was Fenia. Fenia Makhtesyan,” Anzhela sighs.

Methods

One of the oldest methods of slow execution is the use of animals. Say, a person sentenced to death was thrown into a pit with snakes or into a ditch with predators.

FSB treated kidnapped Ukrainian citizens in much the same way. The role of animals, however, was played by Russians, collaborators, and employees of local so-called ‘law enforcement agencies’.

When asked whether FSB representatives were involved in the torture, Ukrainian national police investigator Ihor Demianiuk said that they usually did not use physical force against the kidnapped – they did not get their hands dirty.

“They exerted psychological pressure, played the-good-and-evil-cop game. They gave orders to Russian guardsmen, like ‘Take this one out’, ‘Take that one in’,” Mr Demianiuk explains. “They could say, ‘“Work” with him, he’s not telling the truth.”

Lower-level executives, though, behaved like animals, the investigator says.

“They would get drunk at night and start ‘having fun’. They would make people sing the Russian anthem, strip naked, and crawl on the floor.

“Or they would bring a naked prisoner into a cell, and there would be another naked man with an erect penis… And Russian guardsmen were watching; they liked it.”

“Russians especially liked sexualized violence,” Mr Demianiuk adds, after a brief pause.

He explains in detail one type of torture: Electric shock. When electrodes are connected to a person’s ears and fingers, the effect is the same as when current is applied to the genitals.

“But what they did was they [connected the electrodes] to the genitals and to the anus… to humiliate the victim as much as possible.

“It would be unpleasant for an ordinary person to constantly touch someone else’s genitals… Victims could defecate during such torture.

“You have to really want to do this, to be a pervert. And they [Russians] did it systematically.”

I am talking with Ihor Demianiuk in his office on the premises of the national police in Kherson. It was in the basement of this building that one of the most terrible torture chambers had been organised.

During the occupation of Kherson, the office was used by a Russian Guard chief. In one of the drawers of the desk, the temporary owner of the room found a photo of Mr Demianiuk and gouged out his eyes.

“What can I say,” the investigator shrugs, “this probably shows how intelligent these people are. What else to add here…”

Economic direction

The SBU Kherson office told me what the investigation has established so far.

Each Kherson torture chamber was unique in some way. In one ‘institution’ Russians fed the kidnapped on porridge as salty as brine. In another, they could give 300 millilitres of water per day for several days, instead of food.

In the basement of the commandant’s office, twelve people were held in small cells designed for three convicts. In the former pre-trial detention centre, the largest torture chamber in Kherson, women and men were kept separately. But in the walls of GSB [‘gosudarstvennaya sluzhba bezopasnosti’, ‘state security service’], they were kept together – and the light was never turned off there.

GSB also had an ‘economic’ specialisation. Many Kherson businesspeople and just more or less wealthy residents went through that place. In the eyes of Russian occupiers, ‘wealthy’ were those whose relatives were able to collect at least $1,000 in ransom. The sum would go up to $30,000, not including seized vehicles, icons, jewellery, etc.

By the way, GSB and the GSB torture chamber mean almost the same, since 50 of the 70 members of this criminal organization were somehow involved in the ‘maintenance’ of the basement, and their workplace had the same address. Only ‘General’ Yakymenko’s office was separate, located in a neighboring historic building and connected to the torture chamber by a courtyard.

Mr Yakymenko, who was inclined toward ‘economy’, even introduced an ‘economic security department’ in the GSB, headed by a former policeman from Sevastopol, Oleksiy Suprunenko. Generally speaking, a significant part of Mr Yakymenko’s associates were former ‘anti-corruption specialists,’ ‘tax officers’, and other ‘economic security officials’ from the Russian-occupied Crimea and eastern Ukraine.

“Torture chamber”

Продюсери: Марко Копил, Денис Сігай. Монтаж: Едуард Боев, Дмитро Черкаський. Оператор: Станіслав Огневський

An inscription on the door of one of the basement rooms reads: ‘VIP’. The room’s interior and furniture are no different from the other ones—black cobwebs, a broken chair, bottles of urine in the corner, and pipes to which people were chained. According to one version, the ‘VIP’ cell was mostly used to hold citizens for ransom.

How does it feel to be in such a cell? A notice of suspicion served to Mr Yakymenko, which is cited without the name of the victim below, gives an idea.

…Starting from 06.07.2022 to 14.08.2022, the victim was interrogated repeatedly, in the basement and on the first floor. During the interrogations, the victim was strapped to a chair with plastic fasteners, with a bag over his head, and despite answering the questions, the victim was inflicted with bodily harm, in particular beaten with hands, feet, a plastic stick, wires all over his body, and the back of his head.

In addition, the victim was repeatedly subjected to electric shocks using a pre-prepared device that was connected to his limbs and genitals, while being poured with water. (…) Until the victim was released, he was being starved to death.

…The victim was forced to consent to providing the members of the Kherson Oblast’s GSB with money in the amount of USD 1,000. Then the victim was taken by car to his place of residence (…), where he was released after the transfer of money.”

The GSB torture chamber. Photo: Vadym Petrasyuk

Legal parlance is certainly not capable of conveying the air of the basement, with its colors, smells, and sounds. A detail, though, stands out.

When someone new was brought into the basement, GSB members would start beating a girl in one of the corners.

The girl was taken to the basement for volunteering. Her only fault was that she screamed in a particular way when tortured. The sound of her voice would drive any unprepared person into a state of panic. The torturers loved it. It is possible that it was precisely because of her ability to scream that she was kept in the basement.

Looking at the various objects scattered in the cells and, in particular, the equipment left by the GSB officers and prisoners, it crosses one’s mind that the torturers had an idiosyncratic sense of fun.

There’s a cup with a toothbrush in the corner. Why brush your teeth with not very clean water dripping from a rusty heating system? Probably, for someone it was an opportunity to preserve human dignity in extreme conditions.

On the table is a gas mask for torture. Carefully cut out paper circles are inserted into the eye sockets, and each one has a slightly naive, almost childish drawing of an eye, meaning that before the torture, someone had prepared the props.

The Russian torturers did not like that one of the prisoners spoke with a Ukrainian accent

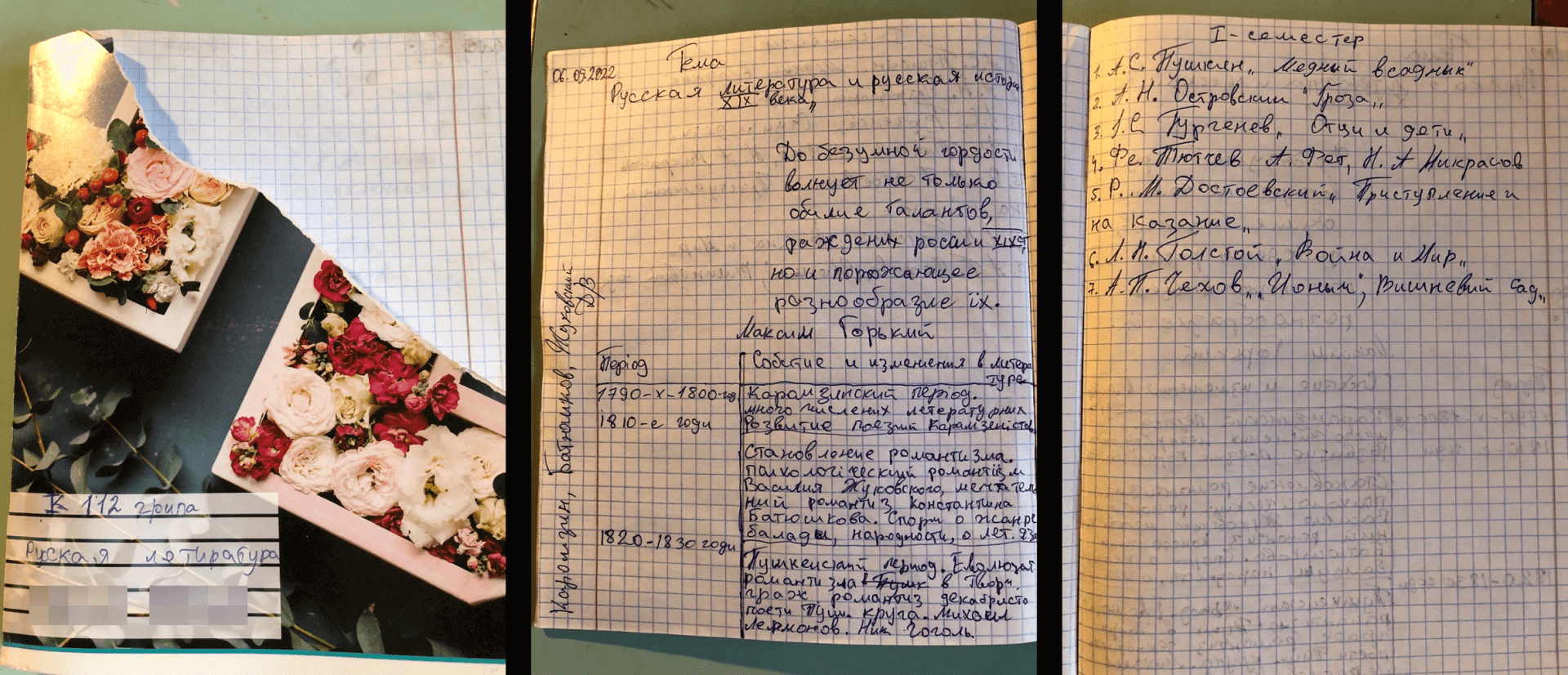

But the most fantastic find is an object that can add a new chapter to the history of torture. It was an ordinary school notebook, with notes on Russian literature.

An SBU investigator explains that the Russian torturers did not like that one of the prisoners spoke with a Ukrainian accent – and they decided to lecture him on fine literature.

All we know about this prisoner is that he was a man in his thirties, whom local wardens believed to be a member of civil resistance. Apparently, he was a special prey of the GSB because the executioners took him away when they fled the city.

The man spent several months in these walls and went through various tortures. Like his cellmates, he was starving, brought to the last stage of exhaustion. In such conditions, the man was forced to take notes on Russian literature, accompanied by screams from the neighbouring rooms.

The synopsis begins with a quote from Maxim Gorky. “It is not only the abundance of talents born by Russia in the nineteenth century that excites one to insane pride, but also their striking variety.” During the first ‘semester’ of study – it is not known how long it lasted – according to the ‘syllabus’, the prisoner was to familiarise himself with the works of Pushkin, Ostrovsky, Turgenev, Tyutchev, Fet, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, and Chekhov.

Here, in different cells, one can really come across books. These are probably the remains of a looted family library of one of the prisoners. One of the warders, who was engaged in ‘educational activities,’ was called ‘Booky’ by the basement residents behind their backs.

The case of the Spider

The household of ‘General’ Yakymenko was, let me remind you, under the direct supervision of Sergei Sinitsyn. At the very start of the creation of the GSB, funds from Moscow for the development of this criminal organisation went through Mr Sinitsyn. But it is unknown whether they went in the opposite direction when the GSB took off and began to systematically kidnap and torture Kherson citizens for ransom.

It is also unknown whether Mr Sinitsyn went down to this particular basement and watched his men ‘work’. At least, the victims did not testify to that. But they sometimes mentioned hearing Mr Yakymenko’s voice. The GSB head was sitting at his desk, watching the torture, and could tell the victim, “You must draw the right conclusions”.

Sinitsyn looked like a coloniser in a cork helmet among a crowd of natives in loincloths against the background of the ‘local elite’ and Russian guardsmen

Colonel Sinitsyn was somehow distanced not only from the ‘low-level’ officers, but also from top collaborators like Messrs Yakymenko and Lipandin. He behaved more professionally and looked like a coloniser in a cork helmet among a crowd of natives in loincloths against the background of the ‘local elite’ and Russian guardsmen.

The secrecy that Mr Sinitsyn-Sabir maintained poses a problem for investigators and prosecutors. It is clear that he not only knew about the torture system, but also directly participated in its planning and creation. However, unless it is proved that he was involved in a specific crime, his actions, from the standpoint of international criminal law, can be qualified as those of an ordinary combatant – as though he was just following orders and is a non-criminal offender.

Does Kherson’s number one executioner have a chance to wash his hands off it, legally speaking? Oleksiy Butenko, a prosecutor of the Kherson regional prosecutor’s office, who supervises the criminal proceedings in Mr Sinitsyn’s case, is very careful in his statements.

“We qualified one fact from his case under Article 438 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, violation of the laws and customs of war. He gave an order to ill-treat a civilian. This is what we have recorded and is confirmed by the materials of the pre-trial investigation,” the prosecutor pauses, probably analysing whether he has said something unnecessary.

“Did he give an order during interrogation?”

“Yes. If you can call it interrogation. It was, in fact, torture. It was disguised as an interrogation. [It was] torture in order to obtain certain information,” Mr Butenko pauses again. “Mr Sinitsyn was not present directly during the infliction of bodily harm, but he was nearby… On another floor.”

“Is this a torture chamber in the main directorate of the national police?”

“Yes. It was the seized building of the main department of the national police, 4 Luteranska Street.”

In other words, the Russian security service officer personally threw a person into a pit with predators.

Opposite 4 Luteranska Street, Kherson is the park where we meet with the SBU investigator who is working on Mr Sinitsyn’s case. What’s special about the city at this time of year is that some chestnut trees are beginning to shed their leaves and, at the same time, bloom.

The Russian security service officer personally threw a man into a pond with crocodiles

In one of the alleys, our conversation turns to an episode when the FSB officer personally ordered to torture a man. Mr Sinitsyn would use euphemisms, like ‘Talk to him properly’.

Looking at the miracle chestnut, the SBU investigator said, “Mr Sinitsyn said something similar… Do you know who that ‘civilian’ was? He was a former SBU officer who did not want to cooperate with the Russians.”

The investigation is ongoing

One day, the truth about the Kherson torture chambers will become history. But today it is not history but the very present.

In the autumn of 2022, the Russian executioners changed their location and fled to the left bank of the Dnieper River. To this day, what happened in Kherson a year ago is happening in all the occupied territories.

The GSB underwent a minor ‘reorganisation’ and, upon instructions from Moscow, dissolved into the FSB. But the overall picture has not changed – same methods, same executioners, and sometimes same victims.

Before fleeing Kherson, the Russian occupiers released some of the kidnapped citizens but took some with them. According to Ihor Demianiuk from the national police, about 20 people were taken from the basement of the main directorate of the police alone to the occupied territory of Ukraine or to Russia. And this is what is known only about one – and not the largest – torture chamber.

The exact number of prisoners taken by the Russian occupiers is unknown

Anastasia Vesilovska, a spokesperson for the Kherson regional prosecutor’s office, recalls that about 1,500 Ukrainian citizens are estimated to have been abducted during the occupation. And this is a very cautious estimate, since the exact number of prisoners taken by the Russian occupiers is unknown.

The fate of 500 to 600 Ukrainian civilians has not yet been established. And just to put into perspective the overall scale of deportation, the Russian occupiers took all 1700 people from a correctional facility.

Ms Vesilovska notes that Kherson torture survivors do not always agree to testify or participate in investigative action. In addition, after the liberation of the city, many of them left, just like other citizens. Today, Kherson is a half-empty city. But the investigation continues.

The trial in absentia in the case of Sergey Sinitsyn has begun in Odesa

Dozens of notices of suspicion have been published by the prosecutor general’s office and SBU, including for Sergey Sinitsyn, Oleksandr Yakymenko, Volodymyr Lipandin, Valeriy Litvin, and other organisers and perpetrators of terror in Kherson Oblast. Indictments against some of them have already been submitted to court.

The trial in absentia in the case of Sergey Sinitsyn has begun in Odesa. In total, the Kherson law enforcement agencies have charged 62 people with crimes against peace, human security, and international law and order, and 53 indictments have been sent to court.

As a rule, it is justice in absentia, that is, without the presence of the accused in court. In absentia proceedings are not a ritual. Anastasia Vesilovska is sure that the in absentia procedure actually brings the time of retribution closer. From time to time, war criminals who have abused the local population, sometimes some of them are taken prisoner, fall into the hands of law enforcement and are sentenced either to 15 years or life in prison.

Such crimes have no statute of limitations. The hunt, which will last for decades, is just beginning, which will involve security services of many countries. Kherson law enforcement officers are also committed to a long and constructive work.

The hunt, which will last for decades, is just beginning

From time to time, the door to the former torture chamber on Pylyp Orlyk Street opens and an SBU investigative team enters with another victim who has agreed to testify. This is a psychologically difficult process, even for the investigator. After all the procedural steps are completed, he goes out on the porch and, without addressing anyone, says, “We will find everyone.”

And this ‘We will find’ sounds so clear – it’s not just something that will be legally recorded, but exactly what it means. From time to time, reports emerge of the assassination or ‘self-killing’ of some of the infamous collaborators. Our sources say that such acts of justice are organised by SBU.

It truly seems that we will find them, wherever they are.

Post scriptum

On November 8, the Malynovskyi District Court of Odesa found the so-called “governor” of Kherson region Volodymyr Saldo guilty of treason and collaboration (Article 111(2), Article 111-1(5), Article 436-2(1) of the Criminal Code of Ukraine). The verdict provides for 15 years in prison with confiscation of property and a ban on holding leadership positions.

This is the maximum possible punishment. As the Criminal Code of Ukraine prohibits life imprisonment for persons over 60 years of age. The trial was held in a special court proceeding in absentia.

Projects is proudly powered by WordPress