Projects

People of the underground

occupied Kherson

Authors: Tamara Balayeva, Dmytro Fionik

Illustrations: Anastasia Ivanova

Layout: Yuliia Vynohradska

To mark the day of Kherson’s liberation from occupation, LIGA.net collected the stories of six members of the resistance movement — of different ages, genders, and with different ways of resistance. They told us what they were doing, why they put themselves in danger every day, and how even torture could not stop them.

How things work

Around mid-2021, the National Resistance Center began training networks of activists in the regions to organize a local resistance movement in the event of a Russian invasion. These were specialists in different areas: plumbers and electricians were taught how to disable administrative buildings, service station workers were taught how to make the occupier’s car drive 200 kilometers after “repair” and break down. They explained why it is important to hang ribbons and paint pro-Ukrainian graffiti in the occupied cities and taught them how to organize this.

Officially, the National Resistance Center under the Command of the Special Operations Forces of the Armed Forces of Ukraine has existed since the beginning of the full-scale invasion, but in fact it has been operating since the adoption of the Law on the Principles of National Resistance in 2021. Even before the invasion, the Center prepared a manual with instructions entitled “Civilian Resistance in the Occupied Territories,” and in the first month of the full-scale war, it was downloaded more than 100,000 times. This figure is the only numerical indicator of the scale of resistance that the Center has. There are no other statistics, because 80% of the resistance was chaotic and emerged spontaneously, without coordination by the Center.

“Resistance operates on multiple levels — through both influencing public discourse and direct physical actions”

In each occupied territory, resistance has stages that are approximately the same for everyone. In the first days of the invasion of any city or community, the invaders were greeted with rallies and protests. This is the first stage, which shows the enemies the general mood of the locals and sometimes gives the Armed Forces time to regroup. It lasts for several weeks, followed by a pause.

This is the stage when locals go underground, and the enemy establishes an atmosphere of terror: conducts the first demonstrative detentions, torture and raids. This continues for several more weeks until the third stage begins: at this time, the locals have a rough understanding of how the terror machine works and launch non-violent resistance in these conditions, such as graffiti, ribbons, and information transfer. At the same time, guerrillas are working in parallel, blowing up the occupiers and collaborators and conducting other sabotage in the physical space.

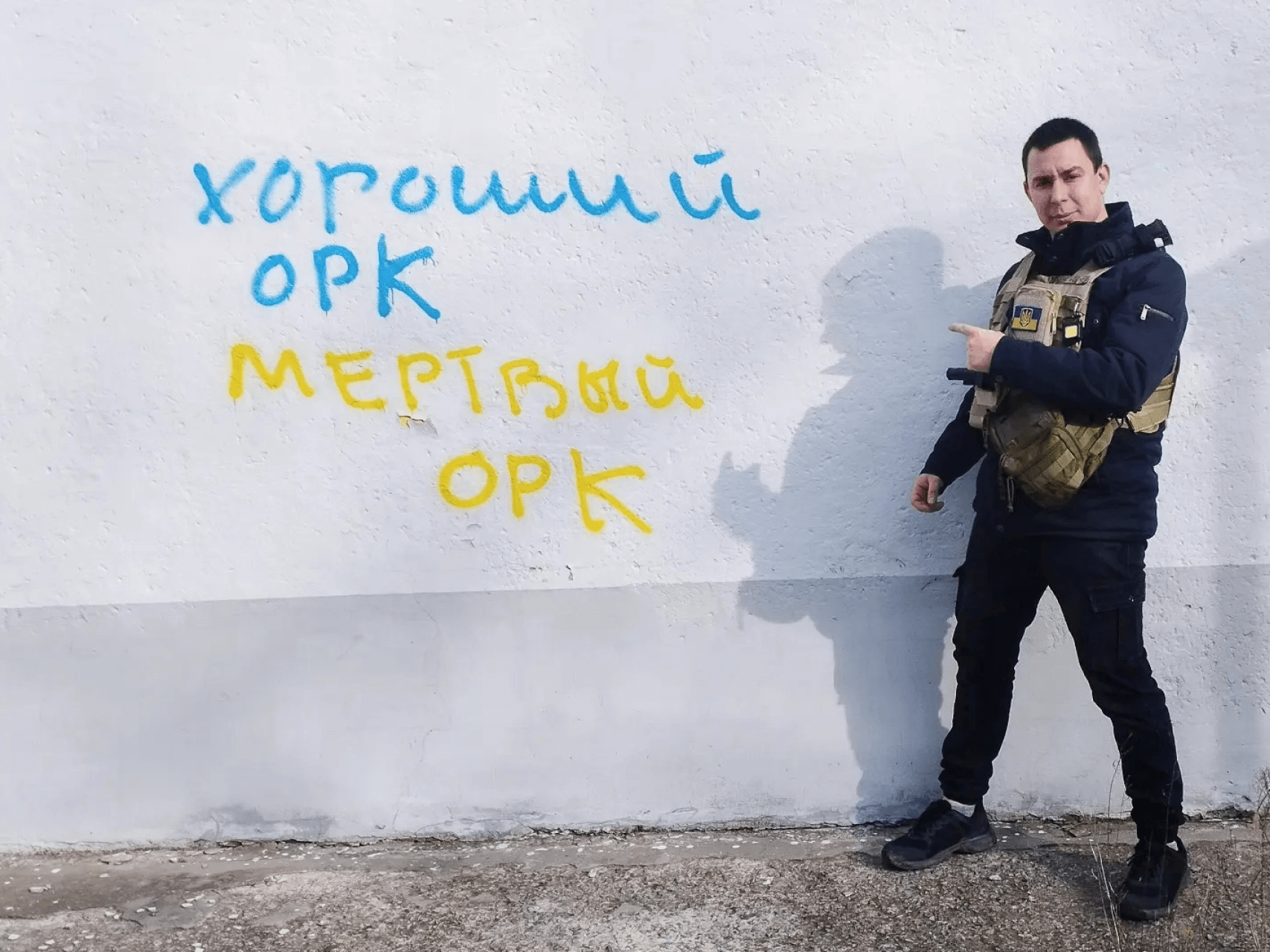

The National Resistance Center says that all components of resistance are important, and one cannot work without the other. “When the enemy enters a community and sees Ukrainian symbols and threats on the walls, it destabilizes them,” the Center explains. “Then they read a Telegram channel and see news that a column of Russian equipment was blown up somewhere or a gauleiter was killed. And at the same time they see a leaflet that says: ‘We know when your shift is. Get ready’. All this works only in combination — creating an atmosphere and physical actions.”

"God, give me strength"

“It’s not scary to die.” As soon as this phrase left Dimka’s mouth, something similar to an earthquake happened: we heard a distant rumble of a series of explosions and everything around us shook a little bit — buildings, road signs, trees. We are talking near the Kherson waterfront. This is the southern part of the city that suffers the most from shelling. There are no passersby or cars.

After the thunder, Dimka’s expression did not change. He seemed to take these sounds as confirmation of his words and continued: “It can happen at any moment. What will happen? Just a flash in front of your eyes — that’s all. That’s not the worst thing.”

The boy looks about 17-18 years old. He is thin. An even more accurate epithet would be emaciated. His face is a bit unusual: his features are correct, but for some reason you want to look away from his gaze. He wears a chain around his neck — a medallion with an icon of the Mother of God. The name Dimka (as his friends call him) suits the guy very well.

This is Dmytro Hudzenko, 24 years old. Last fall, he spent 50 days in the torture chamber of the GSB (the so-called “gosudarstvennaia sluzhba bezopasnosti” — ‘state security service’). Before his detention, he weighed 65 kilograms, after his release — 44. His skin turned gray and his eyes made you want to look away from him. “Dimka hasn’t turned anyone in,” says his friend who arranged this meeting.

“We were saboteurs creating a bad mood for the ‘Russian world’”

On September 4 last year, at about 4:30 p.m., Dmytro Hudzenko, a railroad worker, pinned a Ukrainian flag on the building of the Zahublennyi Svit (“Lost World”) bath and recreation complex. The facility belonged to collaborator Volodymyr Saldo. During the occupation, the occupiers lived there.

“I had to hang the flag here,” Dimka explains briefly. From his story, it is clear that he received the task from a Telegram channel (analogous to the “Yellow Ribbon”). Dmytro did not know almost any of the channel members personally. And this was one of the principles of conspiracy: the less you know, the less risk you put yourself and others at.

“We were saboteurs creating a bad mood for the ‘Russian world’. Very bad,” explains Dimka.

A couple of days before the flag appeared on the building, Ukrainian artillery hit the “Lost World” and several Russian soldiers were killed. The installation of the Ukrainian flag in this particular place symbolized the effective presence of the Ukrainian resistance in the city.

The special operation was divided into two parts and lasted two days. On the first day, one of the participants of the Telegram channel stashed the flag near the “Lost World”. On the second day, Dimka picked it up and installed it.

“Історія одного подвигу”

Продюсери: Марко Копил, Денис Сігай. Монтаж: Едуард Боев, Дмитро Черкаський. Оператор: Станіслав Огневський

Dimka was with his friend. The legend goes that the guys were just walking and drinking beer. When his friend went to the nearest store to get beers, Dima jumped on the fence… Because of the wind, it was a little harder to fix the flag than expected.

The windows of two residential five-story buildings overlook the “Lost World”… “I think the pro-Russian babushkas, who were really fond of their humanitarian aid, immediately reported [us] to the “right place”.

The chase started within a few minutes. The guys fled, jumping over fences, hiding among the buildings of the former shoe factory. His friend was detained before he could get home. Dimka was caught at home.

An ambush was waiting for him. When Dimka began to say that he knew nothing, they brought his friend to him, arranged a kind of confrontation, during which his friend “told all.” According to Dimka, there was no point in lying outright. The so-called “law enforcement officers” found another flag in the room, a flash drive with photos of Russian equipment and… explosives.

“Where did the explosives come from? I found them… It was a beautiful day, I was walking down the street, and I saw an interesting thing lying there.” It is unclear whether Dimka is telling a legend, regurgitating what he came up with during the interrogation, or he is serious. “I found them.” That same evening, the boys were taken to the basement of the GSB.

“There were cases when children betrayed their parents, and parents betrayed their children”

For two weeks, Dmytro Hudzenko was tortured every day. One of the worst tortures was electric shock. “They passed the current through my ears, hands, feet… Few people talk about this, but I will say…” Dima pauses. “And through my groin area. They use forceps like that – they would start laughing… They pour water on me and then again… After the 18th, they didn’t torture me like that anymore. Only hunger, thirst, psychological pressure.”

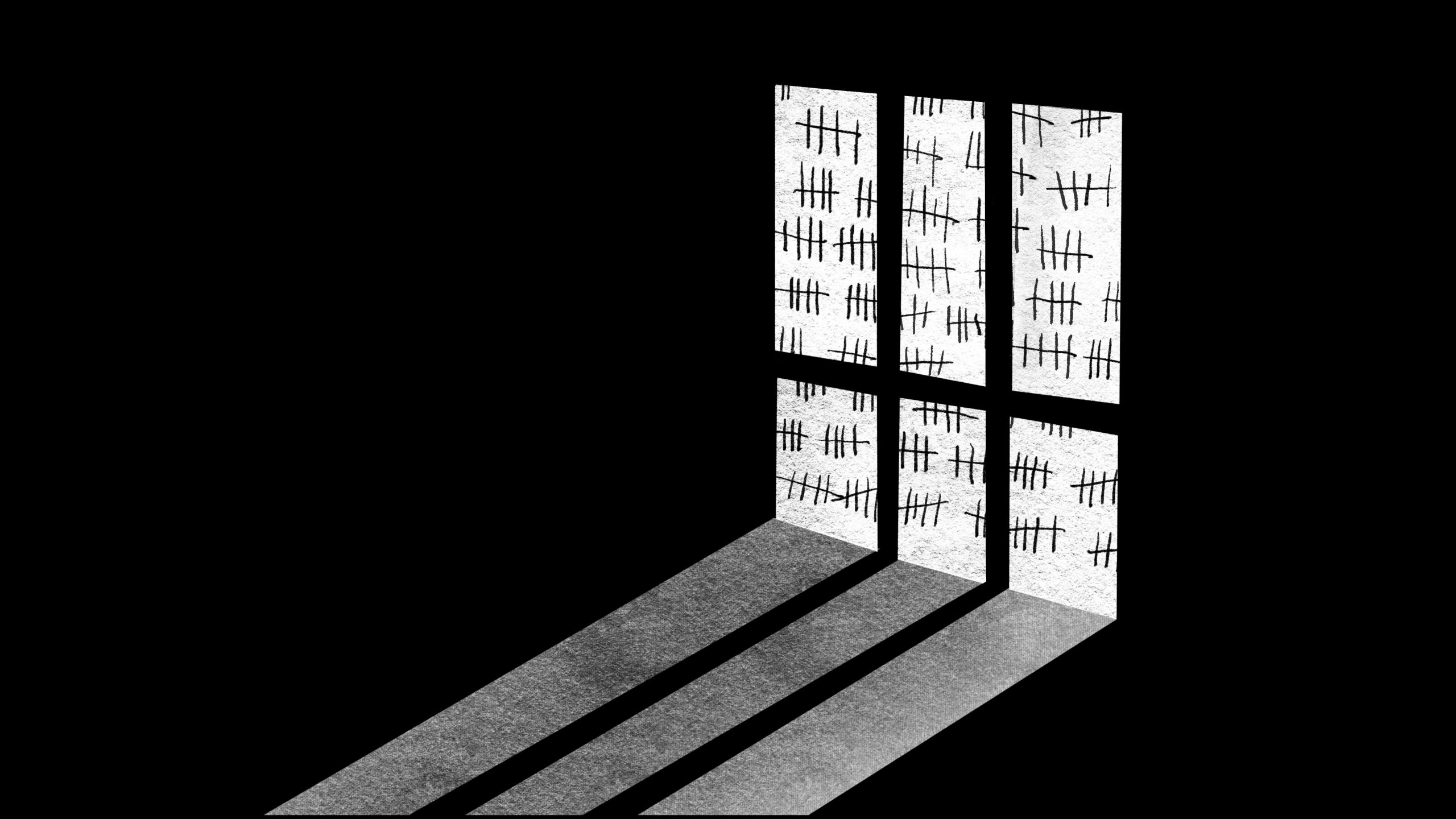

Is it realistic to endure all this? “It’s hard,” says Dimka, “There were cases when children betrayed their parents, and parents betrayed their children. It’s hard to endure. But it is possible.” One of the most famous graffiti on the wall of the GSB torture chamber was written by Dmytro Hudzenko: “God, give me strength”.

Inscriptions on the wall of the GSB torture room. Photo: Dmytro Fionik

The friend who arranged our meeting said that before his detention, “Dimka was an agnostic.” He became a believer inside the cell. He felt the closeness of death several times. In particular, during his release.

When the Ukrainian army approached Kherson, the occupiers transferred some prisoners to the east bank, and released some of them, taking them outside the city and leaving them there. But before that, they made it clear that they were taking them to be shot.

“When the car stopped, they joked: ‘There’s a pit full of them,'” the guy recalls somewhat calmly, “Maybe that’s when I realized that I wasn’t afraid to die…”

When asked if he has forgiven his friend who betrayed him, Dimka answers categorically: “No.”

"Why should I feel sorry for myself?"

When Liliia Aleksandrova woke up from the explosions in Kherson on February 24, 2022, her first thought was: “I want to join the partisans.”

Liliia is 53 years old. She has a disability and gets around with a cane. She has three children: her eldest son is 25 years old, her middle daughter is in her second year of studying to become a physical education teacher, and her youngest son is a tenth grader. Before the invasion, Liliia took care of the house and children, helping her parents. In December 2022, her father broke his leg and became bedridden.

On February 24, Liliia says, “the search for the truth began.” She knew nothing about the existence of resistance movements, but she intuitively searched for like-minded people. She monitored groups on social media, cautiously communicated with locals, trying to find out “who among them does not support the rascists.” She followed the anti-occupation rallies that began in Kherson in March.

“At the end of April, I saw a call on Instagram to write ‘Kherson is Ukraine,'” says Liliia. “It was a call from the Yellow Ribbon resistance movement, and I immediately realized that this was what I had been looking for for two months.”

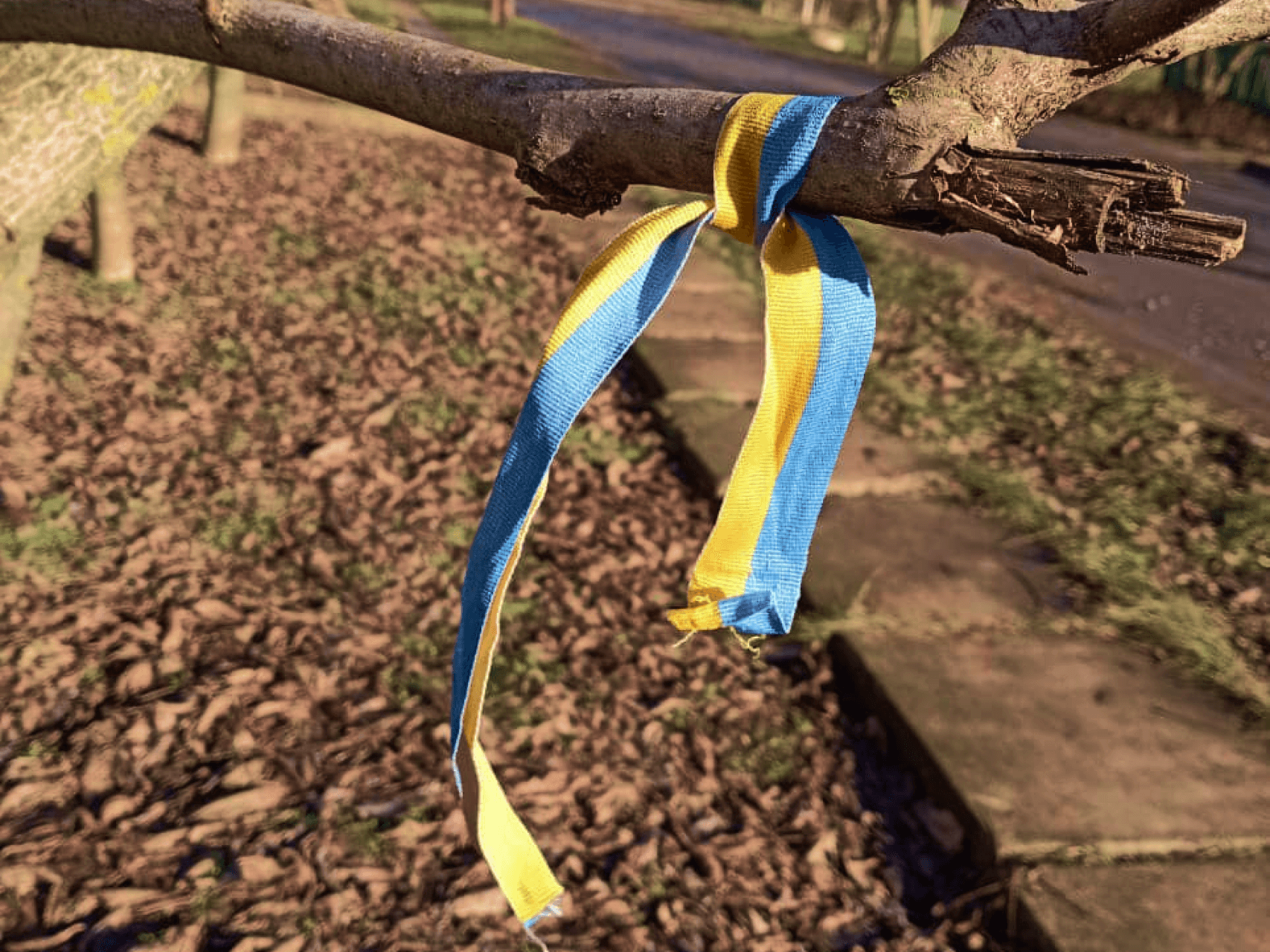

Symbols of resistance in Kherson. Photo: personal archive of Liliia Aleksandrova

Liliia didn’t have any paint, so she started making yellow and yellow-blue ribbons out of old clothes and pinning them to her clothes. Later, she decided to make her first mural on a wall in the street. She bought red paint (“To make it catch their eye”) and wrote on a fence in her neighborhood: “Rascists, go away”. Over the next few days, she made up to ten such inscriptions, tied yellow and blue and yellow ribbons to trees and bushes, and took pictures of them.

“When I had enough photos, I decided to send them to the Yellow Ribbon chatbot and they answered me: ‘This is very strong’,” says Liliia. “But they didn’t start giving me tasks right away, they first checked that I was really a pro-Ukrainian person. I used the Internet to show the guys what I had at home – a flag, a bracelet, ribbons. Then they believed me and started giving me tasks that seemed simple but dangerous. They asked: ‘Can you draw this and that?’ I said that if I could, I would do it.”

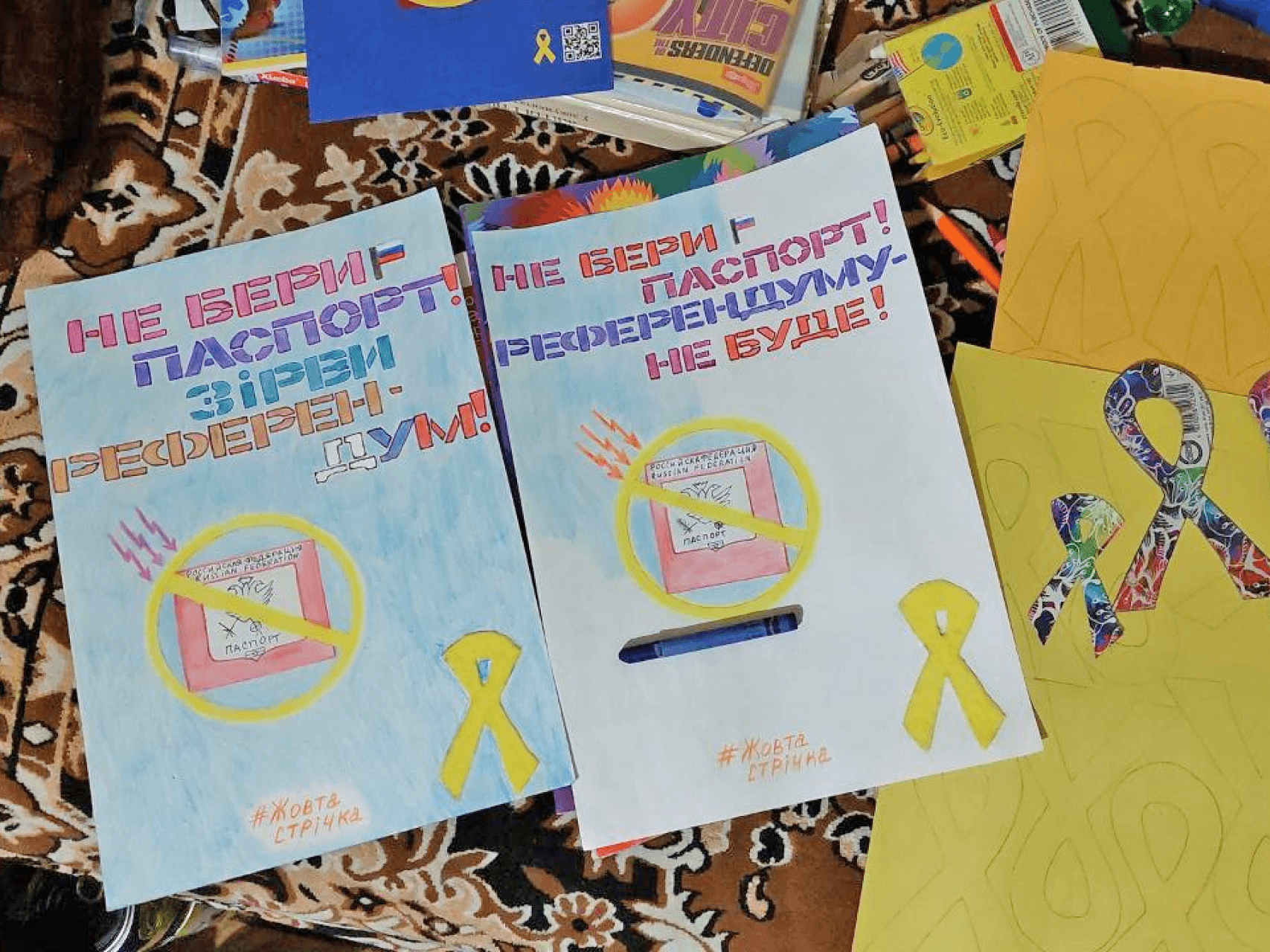

Liliia drew her own postcards during the occupation of Kherson. Photo: personal archive

Gradually, the tasks increased. Liliia bought spray paint and painted yellow and yellow-blue ribbons, then made images of the Ukrainian flag on road sign posts. Later, she started drawing and posting leaflets on the street.

“I had to put as much information as possible on one postcard so I took a long time to draw each postcard,” Liliia recalls. “The most difficult thing was to draw the chicken on the Russian passport, which I then crossed out in red.”

Liliia disguised herself as best she could when she went “on the job”. During the day, she would walk the streets with a cane, as usual because of her sore leg, and in the evening she would leave it at home, put her paints and postcards in a tailor’s bag, and go “to work.”

“Each outing lasted an hour and a half to two hours,” Liliia recalls. “I remember when I painted a sign at a bus stop and just as I was leaving, a rascist patrol in a car appeared from somewhere. But I was lucky. And then there was the time when I started gluing a postcard, and then I saw my uncle coming down from the bridge. He came up to me, and my heart was in my throat, so I didn’t say anything. He looked at the postcard and said: ‘Woman, aren’t you afraid? Take it off, I’ll tear it off anyway’. I took the card off, stood behind the bushes, and then stuck it a little further and took a picture.”

There was a service center of the Ministry of Internal Affairs near Liliia’s home in Kherson. The Russians set up their headquarters there and painted over the Ukrainian coat of arms on the gate. Liliia saw it and immediately decided: “I’m going to paint everything around with Ukrainian flags so that you bastards can see that you are not welcome here.” The next day, she took yellow and blue paint and painted flags on all the signs and traffic signs near the building. She was so scared and shaking, she didn’t finish the last flag and ran home. The next day she came to check and saw Russians looking at one of the road signs.

Liliia Aleksandrova after the liberation of Kherson. Photo: personal archive

After the liberation of Kherson, Liliia became a “star”. Her photo in a bunny hat, taken on November 11 on the main square, went viral. According to the founders of the “Yellow Ribbon”, 80% of the ribbons and postcards hung and painted in the city during the occupation were her work.

Now Liliia is participating in the resistance in the occupied part of Kherson Oblast – not physically, but she is performing other tasks. “During World War II, my grandfather, at the age of 19, first joined the partisans, then was a tanker, refueled airplanes, and was in the infantry. He didn’t feel sorry for himself, so what do I have? If I ended up in the temporarily occupied territories again, I would do the same thing. How else?” says Liliia.

An underground workshop for sewing ribbons

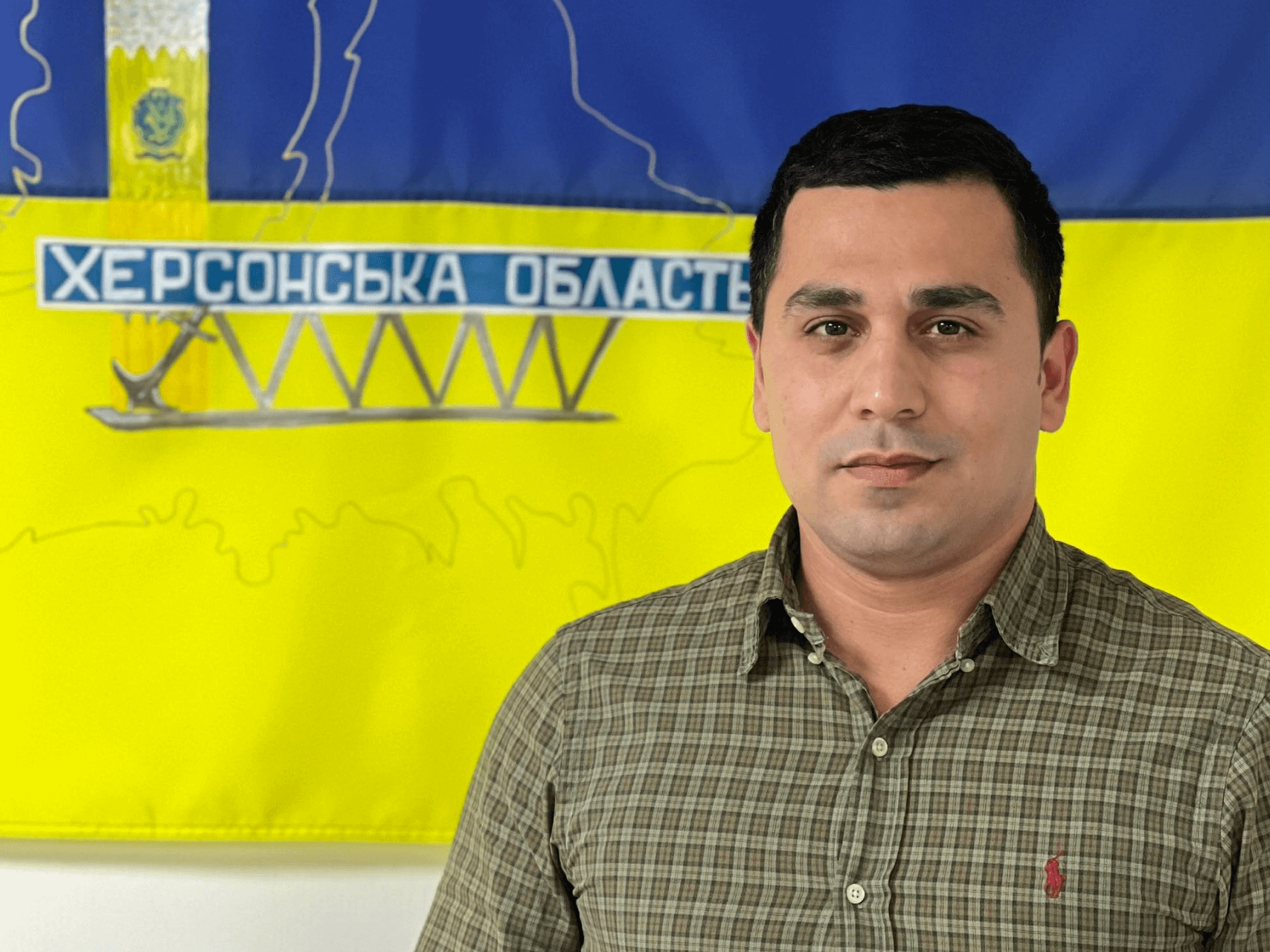

In April 2022, Nisar Ahmad, director of the Municipal Institution for Capital Construction of the Kherson Oblast Council, was hiding at different friends’ places in turn. The city had been under occupation for a month and a half, and recently, friends from law enforcement warned Nisar: “They are looking for you.”

Before that, he decided to stay in the occupation and start working underground. When rallies against the occupation began in Kherson, Nisar helped organize and transport people from the territorial communities. When problems with food arose in March (in particular, there was almost no bread), he found several tons of flour and organized the baking and distribution of bread.

“When I was told that the Russians were looking for me, I was on the street wearing shorts, a T-shirt, slippers, and my car keys. I had nothing else with me, and I realized that I shouldn’t go home – they might be waiting for me there,” Nisar recalls. “My friends clearly instructed me, saying that my car was in the Russian database, so it was better not to drive it. A friend hid it in a garage cooperative, and I started living with different friends in turn. My wife and children had already left Kherson by then.”

The next day after the news of the search, Nisar learned that his house was searched. They broke the door and robbed the apartment. A neighbor saw through the peephole how the Russians were taking away a TV and other equipment.

“When I was told that the Russians were looking for me, I was outside wearing shorts, a T-shirt, without money or documents”

“Until that moment, the Russians had not visited the utility company where I worked,” says Nisar. “So most of the employees were working remotely, but sometimes they came to work. A few days after the ‘search’ in the apartment, the Russians came to work. They interrogated employees and looked for me. We have mostly older women working for us – they did not turn me in. The Russians offered them cooperation, but none of them agreed. Then the occupiers said they were taking this building. No one came to work anymore.”

One day, Nisar came out of the building to another address of his hiding place and saw a yellow and blue unevenly cut cloth on a bush. The occupiers had already taken down the Ukrainian flag from the city council building, and a pall of depression hung over the city. “And then I saw this ribbon and felt a surge of joy. I thought: “Damn, this is so cool! It’s just a piece of fabric, but this is exactly what people under occupation need to see in order not to lose hope.”

Nisar Ahmad set up a yellow and blue ribbon sewing network in the occupied city. Photo: personal archive

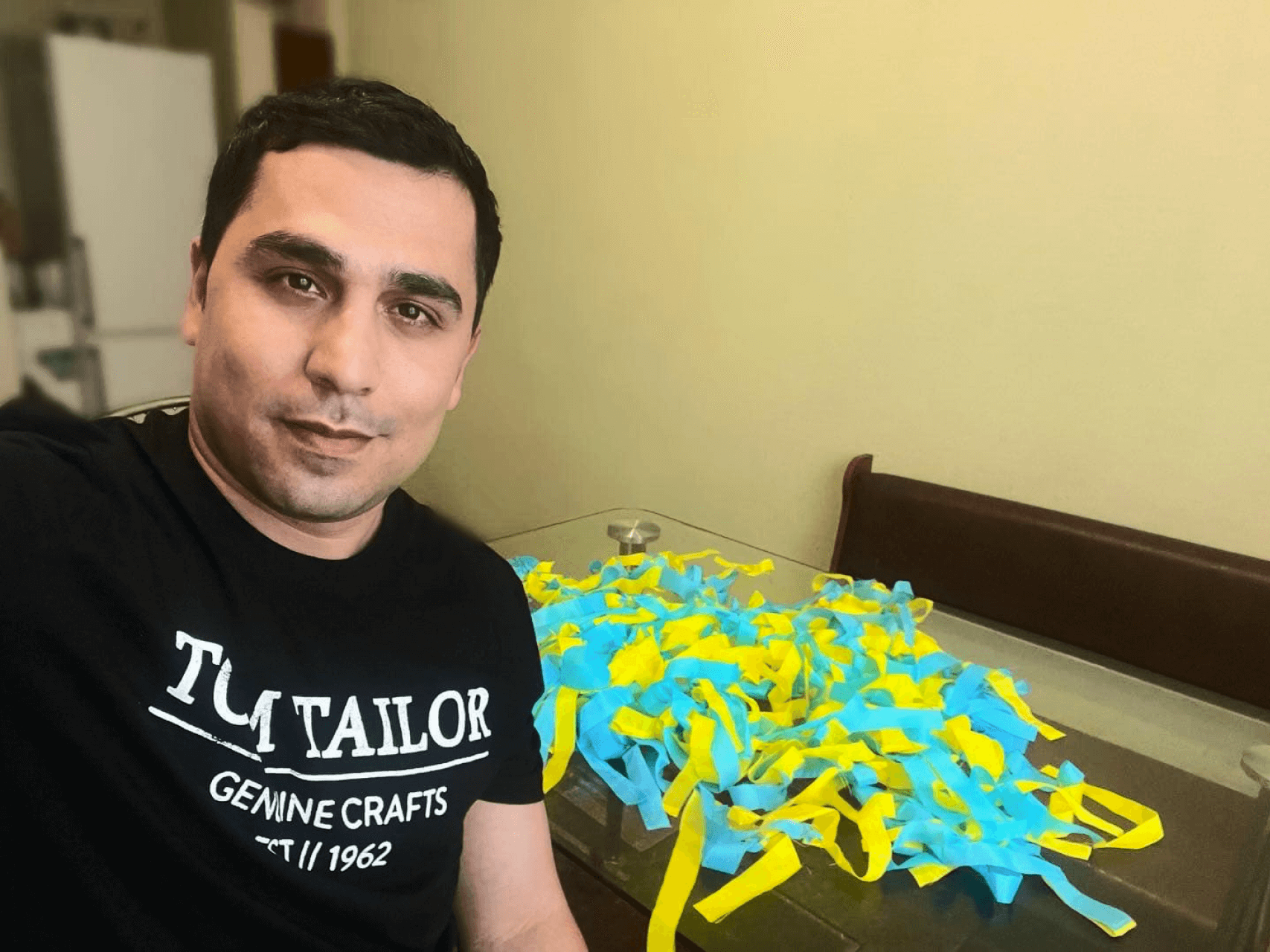

On one of the social networks, Nisar had a chat with like-minded people from Kherson and neighboring communities. He posted his idea there: to find any yellow and blue fabric, cut it into ribbons, sew them together, and hang them around the city. Everyone backed his idea. They organized a meeting on Zoom and began to build a network of ribbon-makers.

“We found yellow and blue fabric separately. It could be anything – T-shirts, towels, curtains, tablecloths,” Nisar recalls. “The mothers and grandmothers of our boys and girls sewed it all together at home, and we made about 200 ribbons a day. Then we hung them up – not only in Kherson, but also in the region.”

Nisar saw how the work of his community and other members of the resistance affected the people of Kherson and the occupiers. Local residents were secretly taking pictures with the ribbons, some of them had tears in their eyes.

The community that Nisar organized sewed about 200 ribbons a day. Photo: personal archive

“I also saw how it affects the mood of the occupiers,” says Nisar. “They came to Kherson self-confident, thinking that they were ‘liberators’. But they quickly realized that this was not the case. All those ribbons and graffiti on the walls intimidated them. They never even walked the streets alone. They always went in a crowd and with weapons.”

In total, Nisar’s community of like-minded people consisted of about 40 people. There were about 10-12 people who were constantly engaged in civil resistance. They were not only involved in the ribbons, but also handed over the coordinates of Russian equipment and troops directly to the SBU via social media chat.

“Two of our guys were detained by the Russians because of this,” says Nisar. “They found these coordinates in their phones. One of them was later released, but the other is still in captivity.”

In early June, Nisar decided to leave the occupied territory. The sewing of yellow and blue ribbons had already been established and could work without him, but he could not physically move around Kherson because he was on the wanted list.

“I asked my friends in law enforcement to evacuate me. They had been planning the operation for some time, and in the first days of June I was able to leave,” he says. “My wife and children and I met in western Ukraine and then moved to Kyiv together.”

Nisar’s fellows continued putting yellow and blue ribbons in the region, even after the city of Kherson was liberated. In the first three months of 2023 alone, they placed about 2,000 ribbons. But recently, they have stopped doing so on the left bank: Most activists have since left for Ukraine-controlled territory, and those who remain try to behave quietly so as not to endanger themselves.

After leaving, Nisar created Support Kherson, a charity that delivers humanitarian aid to the de-occupied territories and operates support hubs in major cities for people who have moved from Kherson Oblast.

“Resistance can be very different,” says Nisar. “It’s very important to do everything you can at your level to charge others with it, so that people don’t lose faith that Ukraine will return. A single ribbon that a person sees on a bush can give them a supply of faith for a month. This is very important, just as it is important not to change yourself.

“My mother-in-law worked in a kindergarten for over 20 years. When the occupiers came there to negotiate cooperation, she simply stopped coming to work. A school director I know went into hiding when they started forcing him to cooperate. Everyone just has to do what they can at their own level.”

47 days in a torture chamber

In early August 2022, Andrii Andriushchenko, 26, was preparing to blow up one of the leaders of the occupying authorities in Kherson. He had everything ready, including explosives and a thought-out plan.

Andrii knew the routes and schedule of his target. He just had to wait for a sign from the case officers in Ukraine-controlled territory and carry out the plan. But on 4 August, Russians found Andrii, who they had been searching for for several months. He was sent to a torture chamber, where he spent 47 days before he managed to escape by a coincidence that resembles a miracle.

Andrii Andriushchenko had worked as an art director of nightclubs for most of his life. On February 25, 2022, he joined an informal people’s guard of Kherson, where some guys and girls gathered in one place and tried to figure out how to resist the Russians and prepare for a possible occupation. Some of them had weapons, some had sticks, and some only enthusiasm.

“If we see more than two guys together in the city, we’ll shoot them”

At first, they were making Czech anti-tank hedgehogs and Molotov cocktails. But in a few days, it became clear that this was a suicide mission that made no sense, because the Russians would attack Kherson with their equipment and would have a lot of weapons.

Then the fellows divided the city districts into squares and started patrolling. They would protect public order, defend hospitals and shops from looters, and collect and transmit information about the Russian enemy’s movements.

A few days later, the Russians came to the place where the Kherson guard was gathering and only said, “If we see more than two guys together in the city, we’ll shoot them.”

The patrols stopped, and it became clear that work had to be organized covertly.

“We took a large canvas of the Ukrainian flag and divided it into many, many ribbons,” Andrii recalls. “At dawn, we went to the park and hung the ribbons there.”

“The park was at the crossroads of the main streets, where Russian columns were constantly moving. So some of the fellows were watching if the Russians were coming. If they did, we were informed through a special app. But in the end, we managed to hang the ribbons almost without any obstacles.”

The rest of the yellow and blue ribbons were hung on the streets, photographed, and shared with the media. Andrii says that the most important thing for them was to convey the message that not only collaborators remained in Kherson but that there was a resistance movement and the city was Ukrainian.

Andrii Andriushchenko participated in the resistance from the first days of the full-scale war. Photo: personal archive

In early May, Ukrainian internet and mobile service connection was all but available in Kherson. Andrii and his fellows felt like they were in a vacuum, and even watching the news became a problem.

“Then we decided to do this. I found points in the city where I could connect to Wi-Fi, contacted my fellows who had gone to the government-controlled territory, and they told me the news and key messages that needed to be spread in Kherson.

“Then we bought spray paint cans and wrote these messages on the city’s buildings. For instance, when the occupiers were preparing a ‘referendum’, our main message to spread was: ‘Fuck off with your referendum’.”

Andrii would paint the slogans in places where the Russian occupiers were gathered or where as many people as possible could see them. He would go to his assignment very early in the morning, before the curfew, without keys, phone, or documents, then would quickly paint and run away.

He would take pictures of his work during the day while in the crowd, send the photos to his friends on Ukraine-controlled territory, who would post them on social media. At the same time, he was collecting information about one of the occupiers, preparing for blowing him up.

“When the occupiers were preparing a ‘referendum’, our main message to spread was: ‘Fuck off with your referendum’”

On the morning of August 4, Andrii was drinking coffee in an underground bar.

“Suddenly, 12 armed men broke in, as I later found out, from one of the units of their defense intelligence,” he recalls. “They put everyone on the floor, shouted my name, and took me to a utility room in the bar. They covered my eyes with a hat and interrogated and beat me for three hours with their feet, chairs, machine guns.”

Andrii has two apartments in Kherson. He lived in one, and the other was his hideout, where he kept bulletproof vests, paints, weapons, and explosives. The Russians searched both.

“They found bulletproof vests, ammunition, firearms rounds. They were looking for weapons, but I didn’t give away where they were,” the man says. “Then they started looking through my phone, and although I had deleted all the photos, they had a device that can restore deleted photos. They saw my ‘work’ and immediately took me to the detention center on Teploenerhetykiv Street.”

Andrii was held in the torture chamber for 47 days. Every day, the Russians interrogated, beat, and tortured him. The torture was bizarre, Andrii recalls. He was beaten with a stun gun; electric shocks were applied to his genitals and ears; his teeth were knocked out; needles were driven under his nails; he was not allowed to sleep or eat; dumbbells were tied to his neck; and he was beaten every day.

“The ‘investigators’ said that I would never be let go,” says Andrii, “that my activities included extremism and terrorism — although they only knew about the writing on the walls; that I would be in a Russian prison but I would not live to see the trial because the other prisoners would kill me.”

On the 47th day of the torture, the man was summoned for interrogation again. There was a new ‘investigator’ there, and as their conversation went on, Andrii realized that the Russian had not been informed of the details of the case, particularly what had been found during the searches in his apartments.

“The new ‘investigator’ asked me to tell him about myself,” says Andrii. “I said that I had only painted the words ‘Glory to Ukraine’, nothing else. To my surprise, I was immediately released. They just put me outside without any documents, phone, or keys.”

At home, Andrii was not recognized by his family. For about a month, he recovered as best he could, sleeping a lot and meeting with friends. He also went into hiding, afraid that the new ‘investigator’ would come to his senses and he would be looked for again.

A month later, Andrii got his breath back and started painting graffiti on the walls again. But he had to give up on blowing up his target. Later, he found out that the Russians had already detained other people involved in the plan.

This continued until 11 November, the day when Kherson was liberated. But even a year later, Andrii had no time to rest and reflect on what had happened to him.

“It was a miracle that I was set free. There was a change of investigator in my case, and he knew nothing about me”

“On 17 November, I helped open the first humanitarian aid center in Kherson, and then several more were opened,” says Andrii. “After a while, I was offered the position of chief humanitarian aid specialist in the military administration, and soon I became the head of this department.”

Andrii works irregular hours and constantly travels around Kherson and Kherson Oblast. If there is shelling with casualties, he goes to help physically and coordinates the work of others. Now, as Russian shelling in Kherson Oblast has intensified, Andrii’s unit is evacuating children from villages near the city. He looks for places to evacuate children, persuades parents, and organizes logistics.

During the occupation, Andrii received the call sign Artist for his inscriptions on the walls. He half-jokingly calls his drawings ‘occupation art’ and is happy to see them on the walls of houses. They remind him that any struggle is not in vain — even if you only have two cans of paint instead of weapons.

The ‘domino effect’ of the resistance movement

Ivan, a man around 26 to 28 years old, is one of the founders of the Yellow Ribbon resistance movement. Before the full-scale invasion, Ivan had been developing databases for agricultural companies and hadn’t thought about civic activism.

In March 2022, Ivan and his friends took part in rallies against the occupation, and a little later, he started painting Ukrainian flags on buildings and hanging yellow ribbons everywhere, which went on to become the main symbol of civic resistance in Kherson.

Around mid-April, the group of friends decided to scale up. They created the Yellow Ribbon Telegram channel, where they published calls to hang ribbons around the city, and later a chatbot appeared where everyone could get a task — from hanging ribbons to spying on Russian collaborators.

Later, people from other temporarily occupied territories started to join the Yellow Ribbon. The network has thousands of activists, with tens, if not hundreds, of thousands of ribbons and graffiti, information campaigns against ‘referendums’ in the occupied territories, and Russian ‘passportization’ and mobilization.

Andrii participated in peaceful and partisan resistance. Photo: personal archive

“There was resistance from the very first days of the invasion,” says Ivan. “Unarmed people stopped Russian equipment, went out to protest, and gathered information about the enemy’s movements.”

“Almost every Ukrainian under occupation has done and is doing this, and it has a significant impact on the course of events. For example, the Yellow Ribbon movement appeared because people were already actively resisting in April 2022, there was a public demand for it, and there was already a rough understanding of how to do it.”

Ivan believes that peaceful resistance can take many forms. It can be a grandmother who refuses to take a Russian pension, or a grandmother who receives a Russian pension but sends it to the Ukrainian Armed Forces. It can be a family that refuses to participate in a pseudo-referendum despite threats. It can be parents who do not take their children to a Russian school but join a Ukrainian one online, or teachers who refuse to teach according to the Russian curriculum and organize underground schools in apartments and churches. Resistance means convincing old ladies on the bench outside their homes that they shouldn’t take a Russian passport, or persuading someone who is hesitant to take a pro-Ukrainian position in a private conversation.

Each of the Yellow Ribbon activists, as well as all members of the civic resistance movement in general, has constantly exposed themselves to the danger of being taken to a torture chamber.

Ivan knows of only one case when this happened to their activist. A woman was caught with a package of yellow ribbons, which she did not even have time to hang, spent three weeks in a torture chamber and never returned to the Yellow Ribbon, asking them to forget about her.

“Because we work anonymously, we cannot identify when someone is really detained and when it is a fake created by the Russians to intimidate us,” Ivan explains. “The occupiers create hundreds of videos of detentions that later turn out to be fake, with fake people.”

“Or what happens — and it’s common now in Crimea — is that a person is detained, talked to, and released, but they [Russians] make a bunch of stories that they captured a terrorist and sentenced him to 50 years in prison.”

In fact, in order to be detained in an occupied city, one does not even need to participate in the resistance movement. It could happen for no reason or on a fake report.

“The Russians are afraid, so they detain everyone,” says Ivan. “They don’t trust anyone and always suspect that a person who seems to be loyal is secretly passing on information about the location of their barracks.”

“For the Russians, every Ukrainian is by definition a saboteur, and everyone must be detained, interrogated, and thrown into the torture chamber.”

“The Russians are afraid, so they detain everyone”

Now that a year has passed since the liberation of Kherson, Ivan highlights what he considers to be the most important thing the Yellow Ribbon movement did during the occupation.

“I am proud of the fact that we organized a rally on April 27. It was the largest, with thousands of people attending. I am also proud that three weeks before the de-occupation, one of our activists raised a flag on a TV tower.

“The actual disruption of the pseudo-referendum: We conducted an information campaign, and the turnout was below one percent. And in general, we managed to keep the faith among Kherson residents and counteract this hopeless ‘Russia is here forever’ message.”

The founders of the Yellow Ribbon did not intend to spread their movement to other occupied regions. However, people there were inspired by the example of Kherson residents, and now there are activists all over Russian-held territory.

“In particular, the resistance movement is actively developing in Crimea, Donetsk, and Luhansk,” says Ivan. “It all started in Kherson, and then it spread to other regions like a domino effect.”

Historical notes

“Some jackass told on me.”

This is how P., a Kherson local historian who spent about a month in a torture chamber, begins his story. He says that on the eve of Russia’s full-scale invasion, during the winter, he lent money to an acquaintance, who repaid the debt with ‘repairs’. Under the occupation, this mutually beneficial relationship deteriorated.

“At some point, I told him I couldn’t do it anymore. It was impossible to withdraw money from the card. I remember when he started asking me when I was going to get a Russian passport. I would send him after the Russian warship.”

The historian sighs and continues: “I realized what these questions were about when five men in camouflage with the chevron ‘A’, which meant ‘anti-terrorist unit’, came to see me.”

The Russian occupiers cut the Gordian knot of complex credit problems. They found the historian’s collection of the diaspora magazine Ukrainian Cossacks from the 1970s and 1980s, souvenir weapons, and other scientific and historical artifacts. This was enough to send him to a torture cell. As a man with the chevron ‘A’ put it, “You will go with us to the sanatorium.”

The historian’s first cellmate turned out to be a Ukrainian war veteran, who was “told on by his relatives” because of a property issue. The veteran told the historian that they were lucky since there had recently been a rotation of wardens.

“Previously, the basement was run by some ‘drug addicts from the DNR’. And now it’s FSB officers who torture only those from whom they can extract ‘useful information’.”

Soon, the Russians threw another man in the cell. When he came to, he said he was the head of a condominium association. He was not a political activist but had many ‘well-wishers’.

That was the fifth time the head of the condominium had been detained.

“Many a Russian detained him, including Chechens and ‘reindeer herders’ [Russian soldiers from Far North regions]… And each time, with worse health consequences. He was just carried into the cell.”

Then, a ‘blind’ man was brought, meaning his face was so bruised he could not open his eyes, the historian explains.

“At first, I thought it was some kind of covert activist. But then it turned out that he was an ordinary shopkeeper from Bilozerka [a village in Kherson Oblast]. Some Russian soldier did not like the way he was served…”

“His face was so bruised he could not open his eyes. He was an ordinary shopkeeper, and some Russian soldier did not like the way he was served”

The historian remembers the first interrogation well. Question number one: “Tell me, my dear local historian, where did Ukrainians come from?” The prisoner started to explain…

He was not tortured, except for the abnormal conditions of detention — like insufficient food, lack of medicines, unsanitary conditions, or constant electric light. It is possible that he was held ‘for the fun of it’.

The interrogations resembled pseudo-scientific debates, in which the ‘investigator’ argued that, for example, Belarusians did not exist, while the historian argued that they did.

“Belarusians and Lithuanians are one people, but there are no more Belarusians, and there will soon be no more Ukrainians. Lithuanians are also Russians, but they don’t know it yet,” the ‘investigator’ would say.

On different days, the historian was interrogated by different investigators. One of them once said, “There are also normal people among Ukrainians, for instance [Volodymyr] Saldo,” meaning the Russian-appointed mayor of Kherson who had served at the same post long before the occupation.

This time, the historian spoke about who Mr Saldo really was and how many historical monuments — including those related to Russian history — he had destroyed during his previous tenures as Kherson mayor.

“There are also normal people among Ukrainians, for instance [Volodymyr] Saldo”

The ‘investigator’ got interested in the dirt on Saldo. A few days later, the historian was made ‘an offer that was difficult to refuse’.

“Historian, you’ll be fucking great! I’ve arranged for you to work in the administration to restore monuments, as you wanted,” the Russian said, adding, “If you refuse, we’ll nullify you.”

The next day, the newly minted ‘culture official’ was taken home and even given most of the things seized during the search.

The historian did not plan to work in the Russian ‘administration’ and spent the next month in hospitals. This did not arouse suspicion, since most of the people who came out of torture cells were admitted to hospitals with various diagnoses.

After being treated, the man hid in his dacha in the country — something that, by the way, many Kherson residents did.

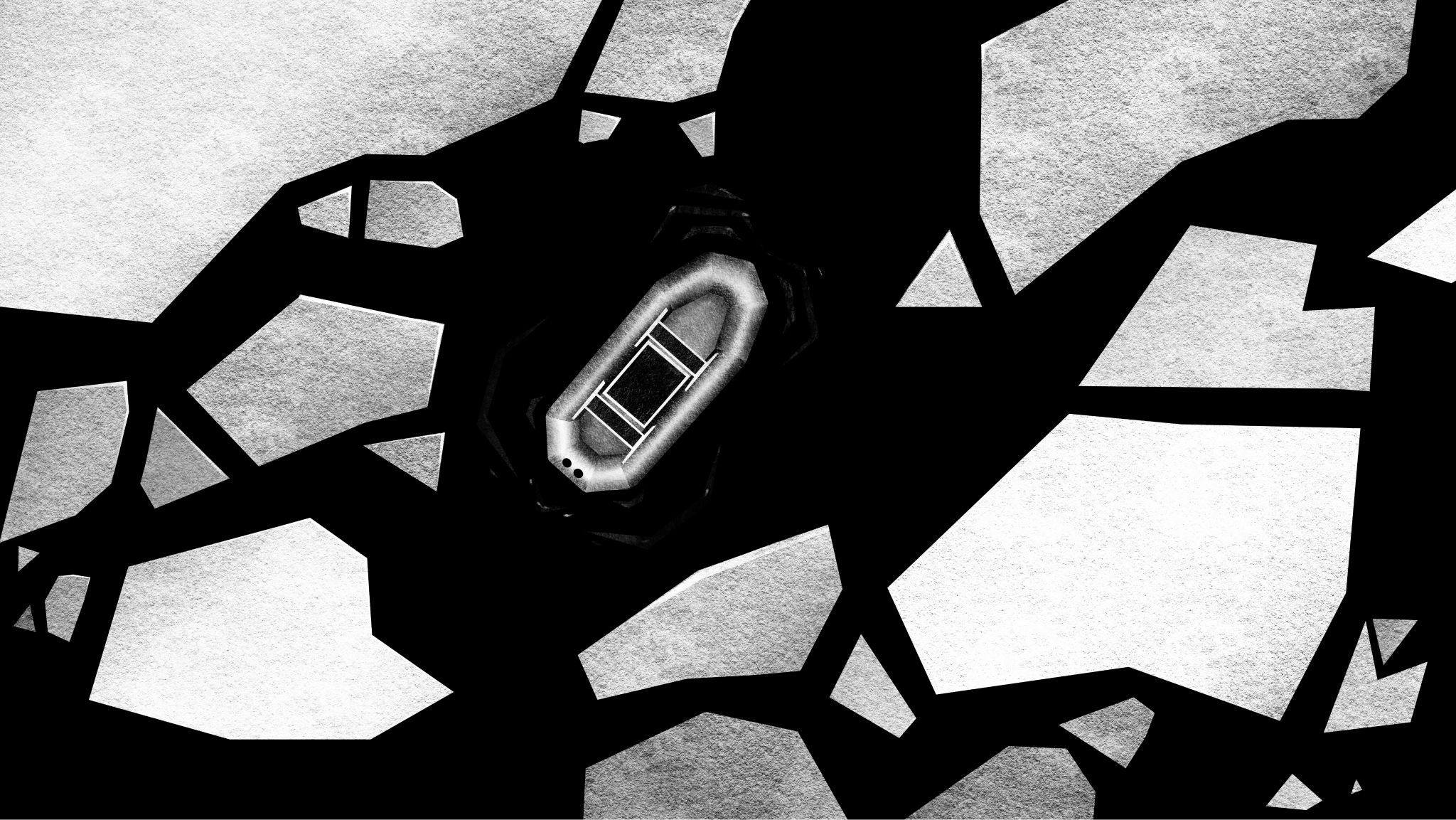

Kherson dachas are scattered on the Dnipro islands. The locals had their own system of keeping safe. Some of them dug ditches from their plots to the labyrinth of streams and kept boats ready to evacuate in case of danger.

Unless absolutely necessary, the Russians did not enter the territory of the dachas because they were afraid. Throughout the entire occupation, Kherson remained a city where the occupiers did not feel like masters.

“Before the liberation, my cat and I were at the dacha,” the historian smiles, “and we survived.”

Projects is proudly powered by WordPress