– It was easy for me. On March 24, my family managed to leave for western Ukraine. That was it. The fear had passed.

Russian soldiers blocked the road at the entrance to the city… I enquired:

– Did you drive this car?

– No, a [Daewoo] Lanos.

– So it was not possible to make out that the governor was behind the wheel?

– No, they had no idea who was in front of them. They took the phone and searched me. They tied my hands behind my back. They pulled the car over to the side themselves. And they took me to the forest. Not too deep. 30-50 meters from the road. There were already several people there with their hands tied, like mine. The soldiers say to us: “It’s your mayor’s fault, we told him that it was pointless to fight back…” Well, here I am: “Guys, you got the jackpot, I’m the mayor.” They were like: “Really, the mayor? ” – “Most certainly”.

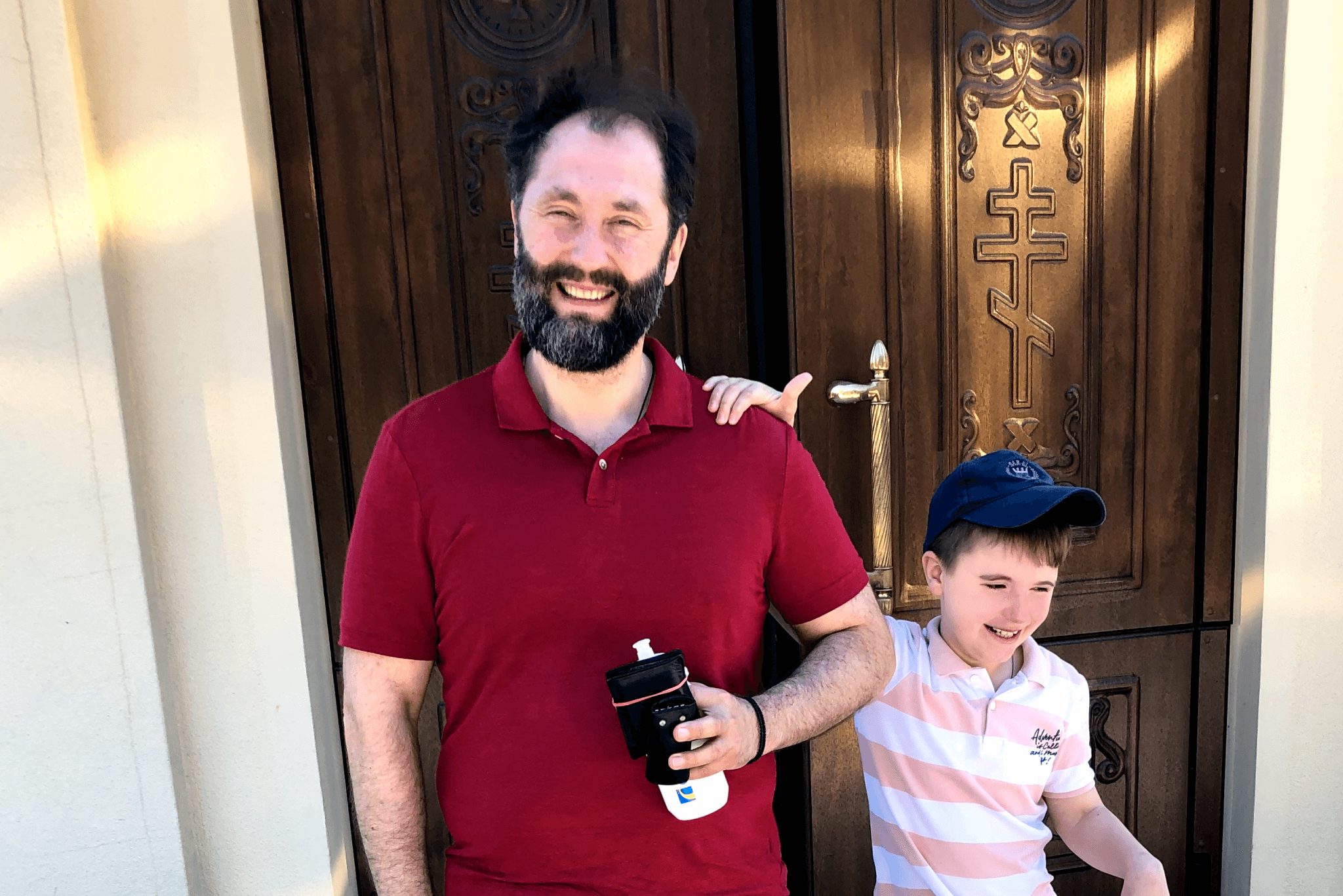

Fomichov smiles and continues:

– And then one of them says: “Can we take a picture with you?” Well, I thought: my hands are tied, what can I do to you? If you want to take a picture, please do. But he asked. I answered: “Yeah, let me take a picture for you.” He goes: “Okay, okay, gotcha.” It seemed like a funny moment, but it is actually important: in order to keep the situation under control, it was necessary to make it clear who is in charge here. And they respect the superiors – it’s their mentality.

There were increasingly more such minor psychological games. The soldiers radioed that they had the mayor. They received an order to deliver him to the commander.

– I had to walk three kilometers under escort. And I had to throw away the phone. I remember I was worried that my wife would call… That’s why I told one of the soldiers: you will hear a call, see such a name, pick up the phone and say three words: “Everything is fine.” Then my wife tells me: “I’m calling you, and someone else’s voice says: “Everything is fine.” And she immediately understood that everything was not fine at all.

Fomichov recalls how a Russian officer looked at a drone footage of the square on a tablet. Shots were sounding from everywhere.

– I ask, why are you shooting? He says: don’t worry, [we’re not shooting] at people. I enquire: are there many people in the square? There are around 500, he says. From the conversation, I understood that their plan included a “clean-up”. Who, I ask, are you going to clean up? Everyone who had weapons, I explain to him, has left. He does not believe, says that there are people in the crowd with machine guns and they will shoot. We agreed on the following: I go with him, I walk in front of him. If shooting starts, I will be the first in line. We got into an armored car and drove off.

Along the way, Fomichov tried to count the enemy’s forces: at the approaches to the city and in the city itself. He counted a dozen units of equipment and several hundred soldiers.

– When we got out of the armored car, I saw people. It was not “five hundred”, there were thousands on the horizon… At that time there were less than 15,000 [people] in Slavutych, and most of them went to the square. When they saw me, they started chanting: mayor, mayor, mayor… The feeling is incredible. Impossible to convey.

Recounting the events of that day, Fomichov mentions the special role of the local priest, who tried to stop the tanks with a crucifix.